The Lobbyist in the Garage

Engine says it’s the voice of startups in government. It serves Google’s corporate interests instead.

Click here to read a PDF of the report.

Introduction

Engine is a San Francisco-based nonprofit that claims to represent the “voice of startups in government.”[1] The group, which also has a lobbying arm called Engine Advocacy, told reporters at its launch in 2011 that it would advocate for startups as a counterweight to lobbying by corporate heavyweights like Google, Verizon and Microsoft.[2]

Evidence suggests, however, that Engine is little more than a creation of the biggest lobbying giant of them all: Google, and its corporate parent, Alphabet Inc.

Messages from the time indicate that Engine was originally created by a Google employee working out of its public policy office in Mountain View, Calif., in conjunction with several former employees of the company. The Google policy manager, Derek Slater, was named as the person organizing Engine by those planning to attend the launch in 2011. The person listed to RSVP for Engine’s launch party was also an employee in Google’s public policy office.[3]

Among the very first people to follow Engine’s new Twitter account when it launched in 2011 were three Google public policy executives—Slater, Adam Kovacevich and Charlie Hale—as well as a policy consultant working for the company.[4] Slater actively recruited members for the group and promoted its campaigns on social media.[5]

Google has disclosed funding the group every year since 2013, though neither says how much of Engine’s budget is covered by the company, either directly or through other groups Google finances.

In practice, Engine has led the charge on a number of policy fights that have benefitted Google—some of which Google did not want to wage in its own name. Earlier this year Google faced a wave of criticism for opposing a bill that would crack down on sex trafficking websites.[6] While Google’s direct opposition was muted, Engine mounted a full-throated effort to oppose the bill. Google’s lobbyists then touted Engine’s statements as a reason to kill the measure.[7]

During the past seven years, Engine has also gone to bat for Google on a number of other policy issues of importance to the company’s bottom line. At a time when Google was facing threats from rivals wielding large patent troves, Engine backed its calls for patent reform.[8] When Congress seemed poised to pass anti-piracy bills that threatened Google’s business model, Engine helped lead the charge that ultimately killed the measures.[9]

Coverage of Engine’s launch emphasized its role as a counterweight to lobbying by corporate heavyweights like Google and Microsoft. But evidence suggests it was midwifed and bankrolled by Google’s lobbyists for the company’s benefit.

Engine has also fought for a number of other Google priorities, including more visas for high-skilled immigrants, radio spectrum reform and stronger net neutrality rules—all key public policy issues for Google.[10] By contrast, Engine has remained silent on issues important to startups, such as access to the platforms that technology giants control, and antitrust.

Of course, other industries have used trade associations to lobby on their behalf, in part to distance their brand names from unpopular policy positions.[11] Google has followed that path by funding trade groups, like the Internet Association, to advance its agenda.[12]

But Google’s creation and financing of Engine is different. Instead of joining a group that represents its interests and those of its peers, Google has used Engine to hide behind startups at a time when the company has little or nothing left in common with that group.

The interests of the proverbial “guy-in-a-garage” long ago diverged from those of the tech giants, to the extent that they are now more likely at odds with each other. “The best start-ups keep being scooped up by the big guys,” noted Farhad Manjoo in The New York Times. “Those that escape face merciless, sometimes unfair competition (their innovations copied, their projects litigated against). And even when the start-ups succeed, the Five still win.”[13]

Google’s Role in Setting Up Engine

Engine says it was founded to help policymakers understand the needs of startups, and help their voices be heard in Washington.[14]Evidence from the time, however, suggests that Google’s public policy manager, Derek Slater, and several other former Google employees and consultants played a key role in setting up the group.[15]

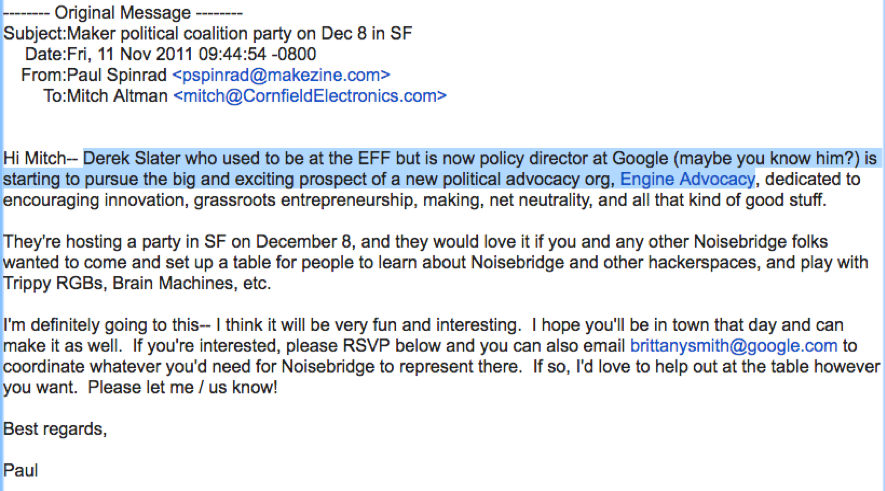

In November 2011, a Bay Area writer pitched a Silicon Valley engineer about the creation of Engine explaining that Slater was “starting to pursue the big and exciting prospect of a new political advocacy org, Engine Advocacy.”[16]

The pitch included an invitation to an Engine kickoff party, sponsored by Google and hosted by another group run by former Googlers.[17] The address to RSVP: brittanysmith@google.com, which appears to correspond to a Google public policy employee, Brittany Smith.[18]

Contemporaneous message suggests Google’s public policy manager set up Engine. The invitation lists another Google policy employee as the contact to RSVP for the launch party.

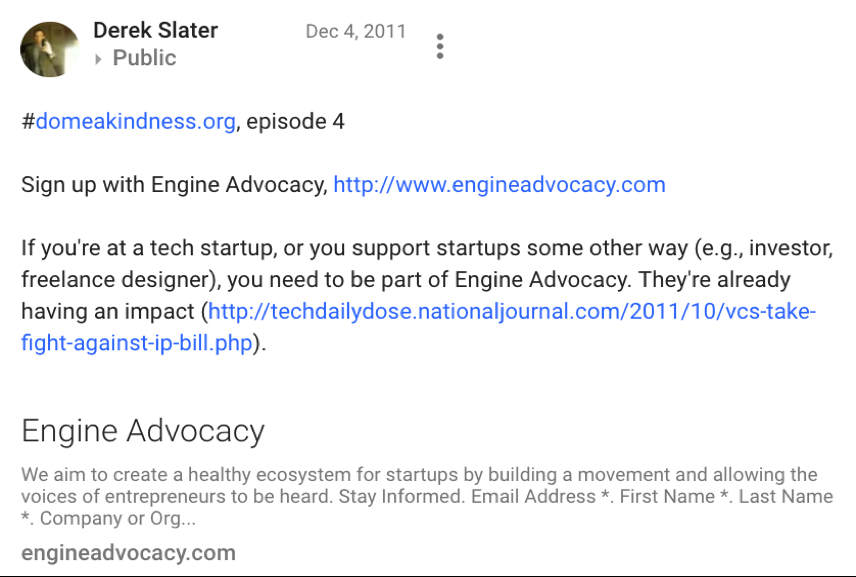

Slater then began to recruit members for the lobbying group and started promoting its content on his Google + account.[19]

Google’s Slater began to recruit members to the group he helped set up and actively promote its initiatives online.

Three Google policy employees and a Google policy consultant were among the first to follow Engine’s twitter account when it launched in September 2011.[20]

Excluding automated spam accounts, follower number eight was Charlie Hale, then a public policy manager at Google X.[21] Follower number nine was Adam Kovacevich, another senior Google public policy executive.[22] Marvin Ammori, a policy consultant whose biggest client at the time was Google, was follower number 10.[23] Google’s Derek Slater was number 11.[24]

In fact, the only followers ahead of the Googler policy executives (and their consultants) were the Engine founders themselves (two of whom were former Googlers), an immigration lawyer, and two politicians, one of which was the twitter account of U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY).

Engine’s public facing persona also relied heavily on people who had come from Google: Two of its three founders had previously worked at the company.

Joshua To helped set up Engine during a hiatus from the company, registering the domain name EngineAdvocacy.com in September 2011, and its current website, engine.is, in January 2012.[25] To had worked as a project manager at Google from 2006 to August 2010.[26] He then returned to work at Google in 2013.[27]

Another Engine founder, Joshua Mendelsohn, also came from Google, where he worked from 2005 to 2009.[28]

Between 2013 and 2015, the only years for which data is available, the two organizations received a combined $4.4 million in contributions.[29] Neither group discloses its donors, but Google disclosed an unspecified amount of support for Engine.[30]

Engine has said it has hundreds of other members including Yelp and Mozilla, though it’s unclear if all those members pay dues or simply filled out an internet form that was circulated by Google and Engine.[31]

Early versions of Engine’s website allowed members to sign up with a simple web form. It’s unclear if any had to pay any dues, or if Google picked up the tab [32]

Google’s Close Ties to Engine

Google’s relationship with Engine runs deep. At about the same time they founded Engine, former Google employees Mendelsohn and To also created a tech incubator, Hattery.[33]

Engine initially shared office space with Hattery, and Hattery paid the salary of Engine’s co-founder and political strategist, Mike McGreary.[34] Google then bought Hattery in the summer of 2013, hiring most of its employees. [35]

Engine shared office space, employees and consultants with Hattery, an incubator started by ex-Googlers that Google later acquired.

Google’s corporate leadership was well aware of Engine’s formation and endorsed it within weeks of its launch. On December 15, 2011, Google co-founder Sergey Brin gave Engine a plug in a Google+ post expressing his opposition to the SOPA-PIPA bills then under consideration in Congress. [36]

Brin included links to the Engine website and a letter organized by the group and signed by the founders of some of Silicon Valley’s largest internet companies. [37]

Google and Engine share a large number of lobbying consultants, one indication of their proximity. For example, Marvin Ammori, an Engine director, is a longtime Google consultant and lobbyist who has described Google as his “largest and most established client.” [38]

The group’s executive director, Evan Engstrom, worked for the San Francisco-based law firm Farella Braun + Martel before joining Engine.[39] The firm specializes in copyright and IP law and counts Google as a client.[40]

Peter Pappas, Engine’s senior advisor on intellectual property and other policy issues, is also an advisor to Google on patent issues.[41] He has drafted white papers on patent reform for Google, and he has worked as a consultant for Google and as a lobbyist for Engine.[42]

Both Engine and Google also employed the S-3 Group as an outside lobbying firm.[43]

Several members of Engine’s board of directors and its advisory board also have financial relationships with Google, and some of them even have experience helping Google harness outside groups to lobby on its behalf.

Hunter Walk, a member of Engine’s advisory board, is a former Google employee.[44] He created several grassroots campaigns for Google, and in 2012 registered a website domain, blackoutsopa.org, to campaign against anti-piracy bills that Google staunchly opposed.[45] Walk has also touted his “experience acquiring start-ups (@Google).”[46]

Brad Feld, another member of Engine’s advisory board, is a co-founder of a venture capital firm that has invested in several companies acquired by Google and co-invested in other tech startups with the company through Google’s investment subsidiaries.[47] Derek Parham, an Engine board member, is a former Google employee.[48] A company he advised, Songza, was sold to Google in 2014.[49]

In addition to direct ties to Google, Engine’s leadership is deeply tied to another nonprofit that Google has funded, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF).[50] Julie Samuels, who became Engine’s chief executive in March 2014, previously worked at EFF.[51] She is married to Engine co-founder Mendelsohn.[52]

Derek Slater, the Google employee who helped set up Engine, also worked at EFF.[53]

The symbiotic relationship between Google and Engine appears to have an open secret among those who worked on its projects.

“Engine works in partnership with Google to advocate for public policies that foster innovation and entrepreneurship,” wrote a designer who helped create an Engine presentation to attendees of the 2012 Republican and Democratic conventions.[54]

Engine’s Lobbying Has Benefitted Google, Not Startups

Engine has consistently lobbied for policy issues important to Google, while claiming to represent the policy interests of small tech startups.[55] Most recently, Engine was a key Google ally in efforts to fight legislation aimed at reforming Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act to hold websites accountable for knowingly facilitating the sex trafficking of underage victims.[56]

Engine’s executive director, Evan Engstrom, testified against the legislation at a congressional hearing.[57] Engine also created a website to serve as a repository of opponents’ arguments against the bills, and organized letters to Congress from Silicon Valley companies.[58]

Engine’s lobbying efforts, however, have dovetailed with Google’s policy priorities from its inception. Derek Slater’s apparent creation of Engine coincided with his larger effort, on behalf of Google, to rally opposition to the SOPA-PIPA anti-piracy bills considered by Congress in 2011 and 2012.[59]

In his online biography, Slater says he was “campaign manager” for the drive against the bills, organizing “grassroots groups” and building “online activism capacity for the company, rallying 7M+ users to oppose SOPA through google.com/takeaction.”[60]

At the time, Google was facing a number of regulatory threats in Washington. Two days before Engine registered its website in September 2011, for instance, Google Chairman Eric Schmidt testified before Congress to defend the company against antitrust charges.[61] Schmidt’s testimony was widely seen as a lackluster defense of the company, and Google substantially stepped-up its lobbying operation following Schmidt’s Congressional appearance.[62]

Engine also supported Google on patent reform—a major issue at the time for the company, which was concerned that its relatively small patent trove might represent a serious legal vulnerability.[63] Only days after a tech consortium sued Google for alleged patent infringement, Engine – along with EFF and the Application Developers Alliance – organized a letter to Congress from venture capital firms calling for comprehensive patent litigation reform.[64]

The group has supported broader allocation of unlicensed spectrum, a key issue for Google, and lavished praise on the company in 2014 for taking a “bold” and “commendable first step” for being one of the first tech companies to release its workplace diversity data.[65]

“While companies are not required to disclose their diversity figures, it is a hope that Google’s example will pressure other big players such as Facebook, Apple, and Twitter to quickly follow suit. Google’s disclosure marks a pivotal moment in Silicon Valley’s agenda: it’s time to start solving the problems of inclusion and access.”[66]

Engine was silent, however, over the company’s multiyear legal battle to withhold its diversity data from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Engine has also filed numerous amicus briefs with the courts on legal issues important to Google, including the Oracle v. Google case, patent and copyright issues and net neutrality.[67] Google’s apparent use of third parties it supports financially to file legal briefs on issues important to the company could run afoul of the spirit, if not the letter, of court rules.

Those rules require amicus petitioners to disclose any external funding intended to finance the preparation of an amicus brief. Google might argue that its payments to Engine are intended as general support, rather than specifically “intended to fund” amicus briefs.[68]

However, in recent years, third parties been chided by the courts for not disclosing relationships with corporate interests in their amicus filings. In 2015, U.S. District Court Judge Liam O’Grady rejected an amicus brief by Public Knowledge and EFF (two groups also funded by Google) in a BMG v. Cox Enterprises copyright case for failing to disclose that the Cox Communications lawyer arguing the case also sat on EFF’s advisory board and helped draft the amicus brief.[69]

“The problem isn’t that you went to EFF and solicited their input and talked to them about whether they were interested in filing an amicus brief. It’s that you didn’t disclose it,” O’Grady said. “And that is, in my belief, disappointing and deceptive. Amicus are obviously friends of the court. And I think with that, there comes an obligation to tell the Court of relationships that they have with a party to an action. You chose not to do it. And I think it’s really unfortunate.”

Engine has also assisted Google during visits to the White House, giving the company’s lobbying efforts the appearance of support from smaller startups. For instance, Engine and Google jointly met with Colleen Chien, a senior White House advisor for intellectual property best known for her work on patent litigation.[70] Google’s General Counsel Kent Walker and Engine’s Josh Mendelsohn, among others, attended the meeting.[71]

The close collaboration between Google and Engine was on display at the Republican National Convention in 2012. TechCrunch detailed the relationship, writing: “Google is not shy about promoting its policy interests. A center rack prominently holds a pamphlet for Engine Advocacy, a new pro-technology political think tank.”[72]

Engine materials were prominently featured at Google’s free coffee shop at the 2012 Republican convention (photo credit: TechCrunch)

Engine has commissioned research papers to bolster Google’s policy goals. Google highlighted one such study, on the importance of high tech jobs to the U.S. economy, on its company blog.[73]

Engine has also helped Google face European regulators, funding research studies in the region that closely align with Google’s lobbying priorities. In 2013, the Engine Research Foundation disclosed on its annual tax form that the nonprofit spent $462,570 to fund several studies on privacy and high-tech employment issues. [74]

In December 2013, Engine released a report by KU Leuven researchers Martin Goos, Jozef Konings, Marieke Vandeweyer, and Engine advisor Ian Hathaway concluding that high-tech workers enjoyed more favorable labor market conditions, lower unemployment, and a substantial wage premium over non-tech workers.[75] The report was funded by Google.[76]

At the same time, Engine has been conspicuously silent about the growing antitrust concerns of the tech startup community even as it increasingly struggles against deep-pocketed companies like Google, Amazon and Facebook. A review of Engine’s website and social media includes nothing about Google’s market dominance or its impact on smaller startups seeking to compete with the company.

The self-proclaimed “engine of innovation” has also been silent about Google’s growing and troubling trend towards killing startup innovation — buying out any tech competitor with technology that represents a threat.[77] While Engine vigorously opposed the mergers of Comcast and Time Warner and even posted an item about the antitrust implications of Facebook’s $1 billion acquisition of Instagram, it was silent about Google’s almost $1 billion purchase of Waze in 2013; its $3.2 billion acquisition of Nest Labs in 2014; and the more than 100 acquisitions Google has made since 2012.[78] [79]

In this respect, the Engine/Google partnership may serve an additional purpose: Helping Google keep tabs on emerging competitive threats as acquisition targets.

Conclusion

Google is one of the most powerful companies in the world, and its efforts to influence Washington match its might. In 2017, Alphabet spent more on lobbying than any other company.[80] Beyond traditional lobbying, though, the technology giant is working to influence Washington through backdoors and alleyways.

Google’s apparent creation and support for Engine is a key indication of the how company uses its wealth to achieve its goals in Washington while hiding behind the curtain. Washington should be aware that while Engine claims to represent startups, the group’s close connections to Google raise questions about whether it is actually serving startups’ interests, or those of the group’s principal corporate sponsor.

[1] Known collectively as Engine, the Engine Research Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, and Engine Advocacy is a 501(c)(4) nonprofit. See http://www.engine.is/about.

[2] Boonsri Dickinson, Hey DC, Listen Up: We Are the Voice of Startups in Silicon Valley, Business Insider, December 9, 2011, available at http://www.businessinsider.com/boonsri-dickinson-dear-dc-listen-up-we-are-the-voice-of-tech-entrepreneurs-in-sv-2011-12.

[3] Brittany Smith, see www.fosi.org/people/brittany-smith/.

[4] CfA compiled a chronological list of Engine’s Twitter followers. See http://www.googletransparencyproject.org/data.

[5] Derek Slater, see archive.fo/uQYa5 and archive.fo/maPkf and twitter.com/EngineOrg/status/137617122632278016.

[6] Nicholas Kristof, Google and Sex Traffickers Like Backpage.com, The New York Times, September 7, 2017, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/opinion/google-backpagecom-sex-traffickers.html.

[7] https://endsexualexploitation.org/wp-content/uploads/Google-Lobbyist-Writing-Congressional-Staffers.pdf; https://www.blog.google/topics/public-policy/googles-fight-against-human-trafficking/.

[8] http://www.engine.is/news/issues/ip/inter-partes-review-keeping-good-patent-policy-strong/5591.

[9] Alex Fitzpatrick, Engine Advocacy Turns Tech Nerds Into Political Experts, Mashable, January 28, 2012, available at https://mashable.com/2012/01/28/engine-advocacy/.

[10] http://www.engine.is/issues.

[11] Linton Weeks, Time For Associations To Trade In Their Past, National Public Radio, May 25, 2011, available at https://www.npr.org/2011/05/25/136646070/time-for-associations-to-trade-in-their-past.

[12] https://internetassociation.org/.

[13] Farhad Manjoo, How the Frightful Five Put Start-Ups in a Lose-Lose Situation, The New York Times, October 18, 2017, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/18/technology/frightful-five-start-ups.html; Olivia Solon, As Tech Companies Get Richer, Is It ‘Game Over’ for Startups, The Guardian, October 20, 2017, available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/oct/20/tech-startups-facebook-amazon-google-apple.

[14] Mark Milian, Josh Mendelsohn, Tech Startups’ Washington Lobbyist, Bloomberg, December 21, 2012, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-12-20/josh-mendelsohn-tech-startups-washington-lobbyist.

[15] https://www.linkedin.com/in/derekslater.

[16] Email from Paul Spinrad to Mitch Altman, November 11, 2011, available at https://tinyurl.com/yb8nu64h or https://archive.fo/6cNz3#selection-1419.0-1423.2.

[17] Two of Engine’s founders also started Hattery, which Google acquired in 2013

[18] https://www.fosi.org/people/brittany-smith/.

[19] Derek Slater, Google+ posts, available at https://archive.fo/uQYa5 and https://archive.fo/maPkf and https://archive.fo/Sk5o1.

[20] CfA compiled a chronological list of Engine’s Twitter followers. See http://www.googletransparencyproject.org/data.

[21] https://www.linkedin.com/in/charliehale/.

[22] https://www.linkedin.com/in/adamkovacevich/.

[23] https://web.archive.org/web/20120111144221/http:/ammorigroup.com/clients-2/.

[24] https://www.linkedin.com/in/derekslater/.

[25] Site Lookup, Domaintools.com.

[26] https://www.linkedin.com/in/joshto/.

[27] Id.

[28] https://www.linkedin.com/in/joshmendelsohn/; Milian, Bloomberg, Dec. 21, 2012.

[29] Engine Advocacy, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2013, filed November 11, 2014, available at https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/ 461064620; Engine Research Foundation, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2013, filed November 11, 2014, available at https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/462820846; Engine Advocacy, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2014, filed October 27, 2015; Engine Advocacy, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2015, filed September 12, 2016; ; Engine Research Foundation, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2014, filed October 27, 2015; Engine Research Foundation, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2015, filed September 12, 2016; Engine Advocacy transferred $1.8 million to the Engine Research Foundation during this period.

[30] https://www.google.com/publicpolicy/transparency.html.

[31] Milian, Bloomberg, Dec. 21, 2012.

[32] https://web.archive.org/web/20140502002403/http://engine.is:80/our-community.

[33] https://www.linkedin.com/in/joshto/; https://www.linkedin.com/in/joshmendelsohn/.

[34] Josh Mendelsohn, Why Investors Must Care About Public Policy, Forbes, April 25, 2013, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/groupthink/2013/04/25/why-investors-must-care-about-public-policy/#bb1be5197871; Hamish McKenzie, Startups Get Political: How Engine Advocacy Is Bridging Washington and the Valley, PandoDaily, September 7, 2012, available at https://pando.com/2012/09/07/ startups-get-political-how-engine-advocacy-is-bridging-washington-and-the-valley/.

[35] Dan Primack, Google Buys Part of Hattery, Fortune, September 19, 2013, available at http://fortune.com/2013/09/19/exclusive-google-buys-part-of-hattery/.

[36] Sergey Brin, Google+, December 15, 2011, available at https://archive.fo/kqnNY#selection-685.116-685.630.

[37] Id.

[38] https://web.archive.org/web/20120111144221/http://ammorigroup.com:80/clients-2/.

[39] http://www.engine.is/news/at-engine/press-release-evan-engstrom-to-become-new-acting-executive-director/6392.

[40] http://www.fbm.com/Stephanie_P_Skaff/.

[41] http://www.engine.is/news/at-engine/meet-peter-pappas-engine-advisor-on-ip/3716; Peter C. Pappas, Resume, available at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/3f0b0c_cb85f73f56584304b308b24f1d5f0f3b.pdf.

[42] https://www.innstrategies.com/.

[43] S-3 Group, First Quarter 2016 Lobbying Disclosure Report on behalf of Engine Advocacy, Secretary of the Senate, Office of Public Records; S-3 Group, First Quarter 2016 Lobbying Disclosure Report on behalf of Google, Secretary of the Senate, Office of Public Records.

[44] https://www.linkedin.com/in/hunterwalk; https://www.crunchbase.com/person/hunter-walk#section-jobs.

[45] https://web.archive.org/web/20120112045129/http://www.blackoutsopa.org/.

[46] https://angel.co/hunterwalk.

[47] http://www.engine.is/about; https://www.feld.com/about; http://avc.com/2007/07/what-google-sho/; Michael Arrington, Google Acquires AdMeld for $400 Million, TechCrunch, June 9, 2011, available at https://techcrunch.com/2011/06/09/google-acquires-admeld-for-400-million/; Leena Rao, Google Ventures, Foundry Group Put $1M In Yesware, Email Tracking And Productivity Platform For Salespeople, TechCrunch, September 27, 2011, available at https://techcrunch.com/2011/09/27/google-ventures-foundry-group-put-1m-in-email-tracking-and-productivity-platform-for-salespeople-yesware/; Barry Schwartz, Trada Secures Additional $9M In Funding From Google Ventures & Foundry Group, Search Engine Land, January 5, 2012, available at https://searchengineland.com/trada-secures-additional-9m-in-funding-from-google-ventures-foundry-group-106762; Revolv Becomes History and Ends Service; Boulder Team Moves to Nest, Denver Post, April 5, 2016, available at https://www.denverpost.com/2016/04/05/ revolv-becomes-history-and-ends-service-boulder-team-moves-to-nest/.

[48] https://www.linkedin.com/in/derek-parham-b7b5504/.

[49] Id.; Jordan Crook, Google Buys Songza, TechCrunch, July 1, 2014, available at https://techcrunch.com/2014/07/01/google-buys-songza/.

[50] Jonathan Taplin, Google’s Disturbing Influence Over Think Tanks, The New York Times, August 30, 2017, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/30/opinion/google-influence-think-tanks.html.

[51] https://www.linkedin.com/in/juliepsamuels/.

[52] Weddings/Celebrations, Julie Samuels and Joshua Mendelsohn, The New York Times, December 22, 2013, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/22/fashion/weddings/julie-samuels-and-joshua-mendelsohn.html.

[53] https://www.linkedin.com/in/derekslater/.

[54] http://www.meetmichellebrook.com/Engine-Advocacy-Tech-Jobs.

[55] http://www.engine.is/issues; McKenzie, PandoDaily, Sept. 7, 2012; Fried, Axios, Feb. 23, 2018; Fitzpatrick, Mashable, Jan. 28, 2012.

[56] Sarah Jeong, Sex Trafficking Bill is Turning into a Proxy War Over Google, The Verge, September 14, 2017, available at https://www.theverge.com/2017/9/14/16308066/sex-trafficking-bill-sesta-google-cda-230; https://www.blog.google/topics/public-policy/googles-fight-against-human-trafficking/.

[57] Evan Engstrom, Online Sex Trafficking and the Communications Decency Act, Written Remarks for House of Representatives Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, Homeland Security and Investigations, October 3, 2017, available at https://judiciary.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Engstrom-Engine-Written-Testimony-10.3.2017-HJC-Hearing.pdf.

[58] http://www.engine.is/news/category/standing-together-to-protect-cda-230; https://230matters.com/.

[59] https://www.linkedin.com/in/derekslater/.

[60] Id.

[61] Hayley Tsukayama, Google’s Eric Schmidt Defends the Company’s Search Practices, The Washington Post, September 21, 2011, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-tech/post/googles-eric-schmidt-defends-the-companys-search-practices/2011/09/21/gIQAR7AllK_blog.html.

[62] Tina Nguyen, Google’s Eric Schmidt Faces Barrage of Questions from Senators, Daily Caller, September 21, 2011, available at http://dailycaller.com/2011/09/21/googles-eric-schmidt-faces-barrage-of-questions-from-senators/; https://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientsum.php?id=D000022008&year=2014.

[63] Jia Lynn Yang, Antitrust Officials Probing Sale of Patents to Google’s Rivals, The Washington Post, July 8, 2011, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/antitrust-officials-probing-sale-of-patents-to-googles-rivals/2011/07/08/gIQANSlZ4H_story.html.

[64] Radhika Sanghani, Microsoft and Apple Sue Google in Patent Wars, The Telegraph, November 1, 2013, available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/google/10419684/Microsoft-and-Apple-sue-Google-in-patent-wars.html; https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2013/07/trolling-effects-taking-patent-trolls-your-help; http://www.engine.is/news/issues/investors-sign-letter-urging-patent-reform/2476.

[65] http://www.engine.is/news/issues/unlicensed-spectrum-can-drive-innovation/198; https://www.fiercewireless.com/tech/google-engineer-wireless-industry-needs-to-break-model-exclusive-spectrum.

[66] http://www.engine.is/news/issues/talent/google-diversity-numbers/3909.

[67] https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/16-341-tsac-EngineAdvocacy-3.pdf; https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/supreme_court_preview/briefs_2016_2017/15-777_amicus_pet_engineadvo.authcheckdam.pdf; https://www.eff.org/document/eff-public-knowledge-and-engine-advocacy-appeals-court-amicus-brief; http://www.engine.is/s/Engine-Net-Neutrality-Amicus-Brief.pdf.

[68] https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frap/rule_29.

[69] BMG Rights Management vs. Cox Enterprises, Inc., Case No. 1:14-cv-1611, Hearing on Motions.

[70] http://law.scu.edu/faculty/profile/chien-colleen/.

[71] http://white-house-logs.insidegov.com/d/b/U31948.

[72] Gregory Ferenstein, The Loudest Voice At A Political Convention Is A Tech Company, TechCrunch, August 31, 2012, available at https://techcrunch.com/2012/08/31/the-loudest-voice-at-a-political-convention-is-a-tech-company/.

[73] https://policybythenumbers.googleblog.com/2012/12/technology-works-importance-of-high.html.

[74] Engine Research Foundation, IRS Form 990, Calendar Year 2013, filed November 11, 2014.

[75] https://www.engine.is/news/research-posts/eu-tech-sector-growth-shows-similar-trends-to-us/2177.

[76] Maarten Goos, Ian Hathaway, Jozef Konings, Marieke Vandeweyer, High-Technology Employment in

the European Union, Viaams Instituut voor Economie en Samenleving, December 2013, available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/571681753c44d835a440c8b5/57323e0ad9fd5607a3d9f66b/57323e0fd9fd5607a3d9f854/1462910479366/FINALEUTECH.pdf?format=original.

[77] http://www.engine.is/news/uncategorized/techdirt-the-engine-of-innovation-realizing-it-can-t-ignore-dc-any-more/22.

[78] http://www.engine.is/news/issues/cpuc-commissioner-proposes-denying-comcast-merger/5274.

[79] https://www.engine.is/news/issues/federal-trade-commission-review-of-facebook-instagram-gives-pause/87.

[80] Hamza Shaban, Google for the First Time Outspent Every Other Company to Influence Washington in 2017, The Washington Post, January 23, 2018, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/01/23/google-outspent-every-other-company-on-federal-lobbying-in-2017/.