Google’s Academic Influence in Europe

Click here to download a PDF of the report.

Executive Summary

Over the past decade, Google has invested heavily in European academic institutions to develop an influential network of friendly academics, paying tens of millions of euros to think tanks, universities and professors that write research papers supporting its business interests.

Those academics and institutions span the length and breadth of Europe, from countries with major influence in European Union policymaking, such as Germany and France, to Eastern European nations like Poland.

Google-funded institutions have published hundreds of papers on issues central to the company’s business, from antitrust enforcement to regulation governing privacy, copyright and the “right to be forgotten.” Events organized by Google-funded institutions have attracted many of the European policymakers charged with creating and enforcing regulation affecting the company.

Google’s European program appears to be modeled on its extensive academic “AstroTurf” campaign in the United States, which CfA detailed in a July 2017 report, Google Academics Inc, and which was detailed in various press reports.[1] However, new research has identified several significant differences in its European program. Taken together, they raise new questions about whether the European Commission has adequate procedures in place to prevent policymakers from being unwittingly influenced by Google’s proxies.

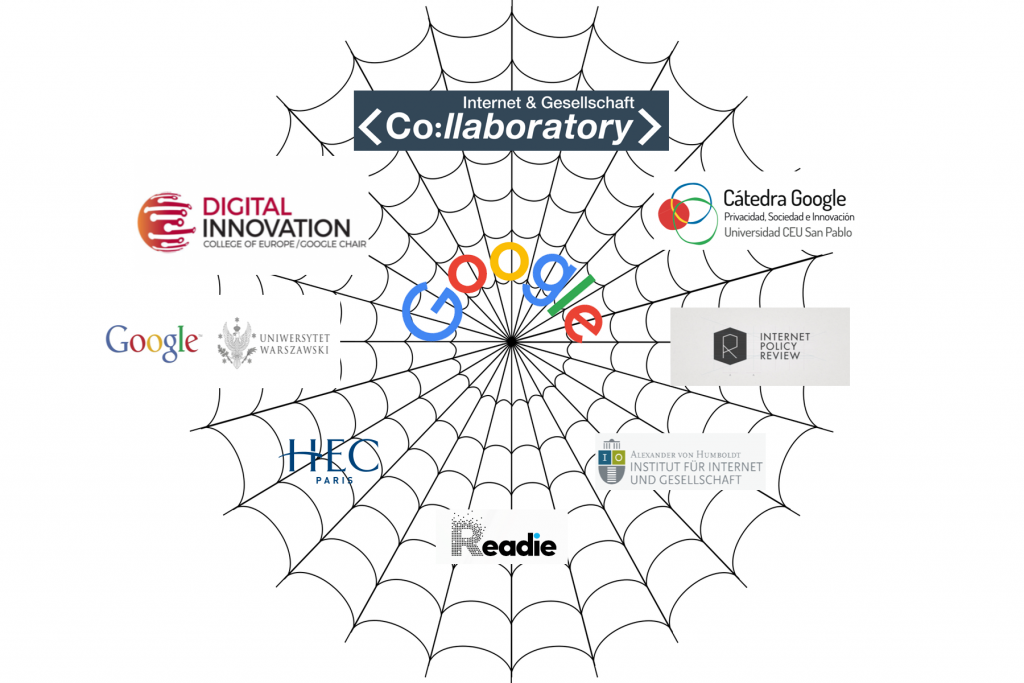

First, Google’s academic influence program in Europe has gone beyond funding existing academic institutions, as it does in the United States, to helping create entirely new institutes and think-tanks in key countries like Germany, France and the United Kingdom. In those countries, executives from Google’s lobbying operation have helped conceive research groups and covered most, or all, of their budgets for years after launch.

Google policy executives have acted as liaisons to steer their research priorities and host public events with policymakers.

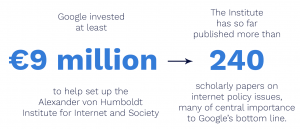

For example, Google has paid at least €9 million to help set up the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG) at Berlin’s Humboldt University.[2] The new group launched in 2011, after German policymakers voiced growing concerns over Google’s accumulated power.[3]

The Institute has so far published more than 240 scholarly papers and reports on internet policy issues, many on issues of central importance to Google’s bottom line.[4] HIIG also runs a Google-funded journal, with which several Google-funded scholars are affiliated, to publish such research.[5]

The Institute’s reach extends beyond Germany, or even Europe. HIIG previously managed, and still participates, in a global Network of Internet and Society Research Centers to coordinate internet policy scholarship.[6] Many are in emerging markets where Google is trying to expand its footprint, such as India and Brazil.[7]

Google also helped establish and fund other similar bodies designed to influence public policies in other key European nations. In the United Kingdom, the company has funded the Research Alliance for a Digital Economy (Readie), which has hosted several policy conferences with European Commission officials and published dozens of articles and publications on policy issues important to Google.[8]

In France, Google helped launch Net:Lab, a similar group that was set up to “provide an open platform for debate involving experts, policymakers and users” and “make concrete proposals to advance the societal, legal, academic and political debate” on technology issues.” [9]

And in Poland, Google has funded the Digital Economy Lab (DELab) at the University of Warsaw, similarly described as an interdisciplinary institute that will research and design policies governing technology issues.[10] Second, Google has created and endowed chairs at higher-learning institutions in European countries including France, Spain, Belgium, and Poland. Those chairs have often been occupied by academics with a track record of producing research that closely aligns with Google’s policy priorities.

Third, Google-financed research and Google-funded academics have become intertwined with research commissioned by the European authorities themselves. In one case, Google and the European Commission jointly financed a study by the Lisbon Council for Economic Competitiveness and Social Renewal that included arguments supporting less restrictive copyright and intellectual property rules, which Google favors.[11]

In another, the European Commission commissioned academics from a Google-funded think-tank to make policy recommendations on whether regulation helps or hampers innovation.[12] The research was cited in a subsequent European Commission policy paper.[13] Such episodes raise questions about whether the European Commission has adequate procedures in place to mitigate potential conflicts of interest.

In Europe, Google has also replicated some of the tactics it has employed in the United States, where it has spent millions of dollars a year to produce favorable policy papers from universities like Stanford and Harvard, and from Washington think-tanks like the New America Foundation.[14]

For example, Google started funding one of Brussels’ most influential think-tanks, the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), in 2014, as the Commission’s antitrust investigation of the company’s practices gained momentum.[15] After Google became a corporate member of CEPS, the think tank’s scholars began participating in panels and publishing a series of policy papers opposing European Commission’s investigations of Google.

For instance, in January 2015, CEPS researcher Andrea Renda participated in a European Parliament forum entitled, “Will Internet monopolies rule our economy in the 21st century?” He opened his remarks by questioning the entire premise, asking: “What Internet monopolies?” Three months later he wrote a paper for CEPS entitled, “Antitrust, Regulation and the Neutrality Trap: A plea for a smart, evidence-based Internet policy.”[16] The paper picked apart arguments by critics of Google that it should not be permitted to favor its own products.[17]

CEPS has also hosted Google-friendly conferences for government leaders.[18] In November 2017, the think tank co-sponsored a forum with the EU’s assembly of local and regional representatives, the European Committee of the Regions, which included a paper by a CEPS fellow and former Google public affairs rep, Bill Echikson.[19] Echikson’s paper touted job creation in Europe by Google and other tech companies, a top priority for the Committee at the time.[20]

Europe’s importance for Google cannot be overstated. It is both a key market, with usage rates above 80 percent in many countries, and the most organized source of opposition to its expansion plans. The European Commission is arguably the only regulator beyond the U.S. with sufficient clout to cause Google to alter its conduct. European officials have levied billions of dollars in fines for antitrust violations and have enacted some of the most stringent laws in the world to protect consumer privacy.[21]

Google’s European academic network helps the company exert a subtle and insidious form of influence on the region’s policymakers, which often goes unnoticed by those who are being influenced.

Google’s German Platform

In 2011, Google helped create a new institute at the prestigious Humboldt University of Berlin, initially accounting for the entirety of its funding.

The German program appears to be modeled on Stanford University’s Center for the Internet & Society, which has created a large body of academic research favorable to Google’s policy positions.

In 2006, Stanford came under criticism for too narrowly tailoring its research to benefit Google’s corporate interests after it received a $2 million donation to write studies on copyright.[22] Both Google and the center’s founder believed copyright was too restrictive. The sponsored department “might as well be the Google Center,” an ethics expert warned at the time.[23]

Yet Google’s influence in establishing the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet & Society (HIIG) five years later was even more direct. Google’s then-chairman, Eric Schmidt, himself first introduced his company’s investment in the German institute in a speech at the university in early 2011, where he explicitly acknowledged his desire to influence the public debate around technology issues:

“We want to actually fund the center, literally to the tune of millions of euros, to discuss and debate the evolution of the web, the Internet, public society, public debate and so forth. And I think that will make the web stronger. I think it will make the German understanding of what’s happening stronger and I think it will make Google stronger by being a participant along with all of the other Internet companies.”[24]

The company inaugurated the new institute in October 2011 with a reception featuring David Drummond, a top Google executive, who addressed more than 400 European politicians, regulators, academics and civil society groups.[25] The launch included seminars on internet governance, global constitutionalism, and media law.

Google’s David Drummond presents Institute for Internet & Society logo to its research directors.

Underscoring Google’s role in creating the institute, Drummond personally presented the new institute’s logo to its four research directors.[26]

During his presentation, Drummond acknowledged the stature of the legal academics overseeing the new Institute noting, “There would be no Google if it weren’t for lawyers,” and spoke of the broader political importance of locating the new Institute in Berlin.

“Berlin is not only the political capital of Germany, which is why we’re so happy to be here and feel like it’s such a great fit for us.” [27]

Google’s David Drummond and German Justice State Secretary Birgit Grundmann at inauguration of Humboldt Institute for Internet & Society.

Speakers at the event included the state secretary for the German justice ministry Birgit Grundmann, who filled in for the German minister of justice and federal protection, Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger. The latter was scheduled to speak the event but was forced to cancel the appearance due to a scheduling conflict.[28]

Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger, a Merkel appointee to the German legal agency responsible for overseeing antitrust, copyright and the “right to be forgotten,” was an official Google had good reason to court. She had previously criticized the company for its “megalomania,” noting, “On the whole, I see a giant monopoly developing, largely unnoticed, similar to Microsoft.”[29]

Three years after her cancelled appearance at HIIG’s launch, Google appointed Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger to its advisory council on the “right to be forgotten” regulation, along with Google executives Eric Schmidt and David Drummond.[30]

“Google was facing several thorny regulatory issues in Germany when it launched the new institute.”

Beyond the growing antitrust sentiment at the European Commission, Google was facing several specific regulatory issues in Germany when it launched the new institute. The year before, the company had admitted to systematically collecting private data from Wi-Fi routers and other information in its Street View mapping project. The collection of that data was a violation of Germany’s strict privacy laws.[31]

The company was also facing increased scrutiny by the German Federal Cartel Office for complaints filed the previous year by Microsoft subsidiary Ciao and the German Newspapers Publishers Association.[32]

Still, Google insisted it would not influence the Institute’s research. “This is not a “Google Institute,” the company wrote in a post. “It is an independent academic body. Google will not interfere with the research.” [33]

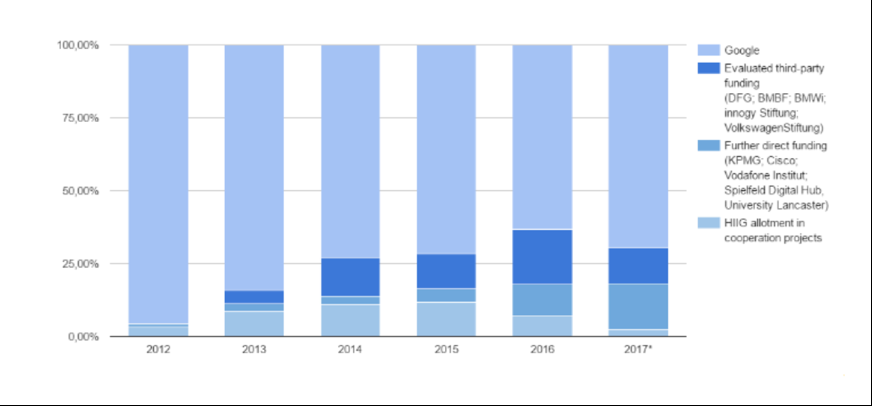

While the total amount of Google’s initial HIIG investment is unclear, financial disclosures show the company has committed at least €9 million through 2019.[34] Six years after founding the institute, Google continues to provide close to three-quarters of its total funding, according to HIIG.

Source: HIIG

The institute also insists its research is not influenced by the fact that so much of its budget comes from a single company. It insists it has “structurally ensured the independence of our research.”[35]

“Of course we will not allow ourselves to be bought,” said Jeanette Hoffman, one of the four directors of the Institute.[36] “That is why we have made an institutional separation and have set up two companies — a funding company serves to finance our work, with the Institute as a research society determining the contents and aims.”[37]

It’s unclear how this structure shields HIIG from the influence of Google’s funding.

The foundation’s purpose is to give the institute topics to research and the financing to carry it out.[38] Yet its independence is called into question by the fact that a Google executive, Wieland Holfelder (Engineering Director Google Germany GmBH) sits on the board of the foundation’s Founder’s Committee.[39]

That committee is responsible for appointing the board and appears to have sway over funding decisions for both the Humboldt Institute and outside nonprofits and academic institutions.[40] The structure also appears to have been used to shield the institute from public records requests about its funding from journalists and public interest groups.

Google has participated in the institute’s events, at which key policymakers are often in attendance. In September 2012, for example, Google provided €30,000 in funding for a two-day conference with the German foreign ministry, attended by more than 100 government officials and academics, to discuss the topic of “Internet Human Rights.”[41] One of the ministry officials who helped organize the event was himself a former Google lobbyist.[42]

Much of the conference discussion focused on the positive role social networks played in the Arab revolutions, according to a Der Spiegel account of the event. It noted that the most prominent guest, German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle, largely echoed Google’s preferences that self-regulation and a multi-stakeholder approach were preferable to government regulation.[43]

Another prominent speaker was Birgit Grundmann, the state secretary from Germany’s federal ministry of justice, who spoke at the launch of the Humboldt Institute only a year earlier.[44]

Several former Googlers have passed through Humboldt Institute. Doctoral researcher Jessica Schmeiss worked for Google Germany for four years before joining the Humboldt Institute.[45] And Humboldt Institute researchers Engin Bozdag and Tiffany Quach both previously held public policy and legal positions with Google.[46]

Underlining its influence, Google has appointed one of its German executives to act as a liaison with Humboldt Institute. Max Senges, who worked in Google’s German public policy office on “Internet policy and academic relations” and serves as a “strategic advisor for Google policy research projects” to the Humboldt Institute.[47]

In his LinkedIn profile, Senges says that, in addition to managing academic relations for the company, he acted as “Google lead for planning, launching and managing the relation with the independent Humboldt Institute for Internet & Society.”[48] Senges was well-positioned to mimic the successful arrangement Google had established with Stanford. While working at Google, Senges was a non-resident visiting fellow at the Stanford Center for Democracy Development, and the Rule of Law.[49]

Google’s HIIG investment pays dividends

HIIG has held more than 160 events and produced more than 240 scholarly papers including many on policy issues important to Google.[50] The seminars, gathering politicians, lawyers, and regulators, address a range of Google’s policy and business priorities in Germany.

To be sure, not all papers by the institute reflect Google’s preferred policy outcomes, and many of the scholars involved are respected scholars that employ sound methodologies. However, a review of the event titles reveals how the institute is shaping policy on a range of issues of critical importance to the company, including data protection, privacy and copyright enforcement. [51] The institute’s published papers have touched on a range of issues of central importance to Google’s business, including the “right to be forgotten,” cloud computing regulation and Google Books.

Few of the institute’s scholars include any disclosure of the company’s financial support of the Humboldt Institute in their papers.

HIIG creates its own research network

In mid-2013, according to domain registration records, Humboldt launched the Internet Policy Review (IPR) to track government regulation of the internet, and later, to serve as a repository for academic research on policy, according to the website.[52]

The publication’s staff consists of a five-member managing board overseeing the journal. IPR also maintains an editorial board made up of researchers, several of whom have close financial and professional ties to Google:

- Lilian Edwards is the chair of E-Governance at the U.K.’s Strathclyde University and a Google consultant.[53] She has written numerous papers and studies on issues related to copyright, privacy, and other policy issues. She has also co-authored reports for the European Union, representing potential conflicts of interest, to be further discussed below.

- Mauricio Borghi is a professor of law at Bournemouth University in the U.K. and the current director of the Centre for Intellectual Property Policy and Management. [54] Borghi was a recipient of a Google Faculty Research Award in 2014 for enhancing access to digitized books.[55]

- Joe Karaganis is the vice president of The American Assembly, a public policy institute at Columbia University.[56] He has received two research awards from Google to write papers on copyright issues of interest to the company.[57]

- Federico Morando has served as the managing director of the Italy-based Nexa Center for Internet and Society at the Polytechnic University of Turin and is currently a fellow there.[58] Since 2009, the Nexa Center has received approximately €175,000 in Google funding for projects related to copyright and Internet freedom, a joint project with the New America Foundation, which has received $21 million from Google and its executives.[59]

Since its founding in 2013, IPR has published scores of articles and papers on its website. Many are written by Google-funded academics—sometimes even directly by Google employees. Daphne Keller, a former Google executive at the Google-funded Stanford Center for the Internet & Society, for example, has published six articles in IPR.[60] Two studies by Andy Yee, who worked as a public policy analyst for Google at the time, were also published by IPR.[61]

Both authors disclosed their direct connections to Google in their papers. However, papers by authors from institutes funded by Google usually failed to disclose that fact.[62]

And other papers did not disclose the fact that the journal’s parent institute is funded by Google, or that many of its editors have connections to the company.

Technical University of Munich, Germany

More recently, Google announced another German university partnership with the Technical University of Munich (TUM) for joint research projects related to artificial intelligence and the “promotion of innovation.”[63]

Announced in February 2018 by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, TUM is set to receive at least €1.25 million over the next three years through the University’s foundation to support TUM academic research. Joining Schmidt at the announcement was Wieland Holfelder, a Google Munich executive and also a board member of the foundation for HIIG.[64]

Google Chairs and Digital Labs

The Internet & Society Collaboratory (CoLab) – Germany

Google’s German policy executive, Max Senges, was also responsible for an earlier apparent attempt to mimic the Stanford model in Germany. In 2010, the Google policy manager launched the Internet & Society Collaboratory (or “CoLab”), which held events and published more papers on topics of interest to Google.[65]

For example, CoLab co-partnered with the Humboldt Institute each year to host its “Telemedicus” Conference, an annual summer symposium focused on internet public policy and legal issues.[66]

Google almost entirely funded CoLab’s operations in its early years.[67] The group appears to have been unable to raise money from other sources as Google shifted its investment to Humboldt, and CoLab ceased operations in 2017 due to lack of funding.[68]

Net:Lab – France

In early 2012, Google expanded the CoLab concept to France, launching Net:Lab.[69] Like the similar organization in Germany, the Paris-based academic initiative was set up to “provide an open platform for debate involving experts, policymakers and users” and “make concrete proposals to advance the societal, legal, academic and political debate” on technology issues.”[70] The Net:Lab charter explained that a key focus of the organization was collaboration between civil society, academics and the private sector to “contribute to the public debate…on the present and future of the internet.”[71]

The nonprofit’s steering committee included French academics, journalists and career diplomats, and a Google employee, Florian Maganza.[72]

Another steering committee member, Cédric Manara, wrote a 2012 paper funded by Google before joining the company in 2013 as senior copyright counsel.[73] He also received a Google research award in 2010.[74]

Digital Economy Lab (DELab) – Poland

In early 2014, according to domain registration records, Google expanded its academic relationships in Europe further East, creating the Digital Economy Lab (DELab) at the University of Warsaw.

The program is described as an interdisciplinary institute funded by Google for the implementation of programs concerning the social, economic and cultural consequences of technology.[75]

There is little public information about the extent of the partnership, or the amount of Google’s funding. However, the DELab website does offer some clues.

DELab’s director, Katarzyna Śledziewska, has a distinguished career in European policy and academic circles.[76] She also serves as a member of another Google-funded initiative, the Readie-Europe Research Alliance for a Digital Economy described elsewhere in this report.[77]

“Google@HEC Chair” – France

In addition to financing institutes and policy reviews, Google has also funded positions for senior faculty members to steer policy at their universities. In 2012, the company announced its first ever business school “Google Chair,” an academic partnership with HEC Paris—regarded as one of the world’s most prestigious business schools.[78]

At first glance, the new position appeared to focus primarily on digital entrepreneurship and business skills over public policy issues. The press announcement noted that the new initiative would offer classes in digital economy; workshops, “start-up weekends” and Google creativity talks. The business school’s website does not disclose the amount of funding Google has provided the program. [79]

The Google Chair on Privacy, Society and Innovation at the Universidad CEU San Pablo – Spain

In June 2012, five months after its French foray, Google established its second “Google Chair” in Spain at the Universidad CEU San Pablo law school.[80]

A Google Spain blog post announcing the deal noted that the Google Chair would offer a “national point of reference…related to the proper legal framework of the Internet, freedom of expression, privacy, transparency and intellectual property.”[81]

The post also revealed that José Luis Piñar, a law professor at CEU San Pablo, would oversee the new Google Chair. Google’s choice of Piñar to chair the new initiative was another strategically useful decision. In 2010, a Spanish citizen lodged a complaint with the Spanish Agency of Data Protection, demanding that Google remove his personal information from its search engine.[82] The agency upheld the complaint against Google and called for the company to remove the links.

Google appealed the decision, initially with the National High Court of Spain, and ultimately with the European Court of Justice. But in May 2014, the European court ruled that search engines could indeed be ordered to remove links from their search results.[83]

In 2014, Google appointed Piñar to its advisory council on the Right to be Forgotten.[84] He has since become a harsh critic of the May 2014 European ruling, arguing that the new rules are ineffective. Users, he said, can simply use other search engines to find the information, and he expressed doubt that the ruling would do anything to clarify the scope of European privacy.[85]

Google Chair José Luis Piñar with Google Chairman Eric Schmidt at 2014 Right to be Forgotten meeting Madrid.

Each year since it was established, the Google Chair at CEU San Pablo has organized an international conference comprised of legal scholars and politicians to address policy issues relating to the internet.

On June 29, 2017 for example, the Google Chair hosted its fifth annual conference, entitled “Law and Technological innovation before the new European privacy framework.” The gatherings have been a valuable place for Google executives to rub shoulders with the Spanish officials charged with regulating privacy and other aspects of Google’s business.

Spanish officials that attended included Aurea Roldan, an undersecretary with Spain’s justice ministry, Angels Barbara i Fondevila, director of the Catalan agency for data protection, and Jose Amerigo Alonso, the technical secretary general of Spain’s justice ministry.

Google executives who gave talks at the event included Francisco Ruiz Antón, Google’s director of policy and public affairs for Spain and Portugal, and Richard Salgado, Google’s global director of information security.[86]

The Google Chair in Digital Innovation, College of Europe – Belgium

In November 2016, Google signed an agreement with the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium to create the “Google Chair in Digital Innovation.”[87] The agreement, signed by the College of Europe’s rector, Jörg Monar and Google’s Brussels lobbyist Lie Junius established a new course on “Policies for Digital Innovation” at the College’s Department of European Economic Studies.[88]

Following San Pablo, the College of Europe also established an annual conference on digital innovation to be organized at the Bruges campus, with the first conference scheduled for April 2018. Topics covered by the new Google-funded program align with the company’s European policy priorities, according to a description of the program, including courses on “the data driven economy,” artificial intelligence and “EU policies for digital innovation.”[89]

Google chose a reliable ally in the in academic world for the post: Andrea Renda, CEPS’ head of regulatory policy, described elsewhere in this report.[90]

The College of Europe has long been known as a training ground for future members of the European Union bureaucracy. Alumni of the College include Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt, Finnish prime minister Alexander Stubb and British deputy prime minister Nick Clegg.[91]

College of Europe Rector Jörg Monar signs agreement with Google’s Brussels lobbyist Lie Junius for “Google Chair in Digital Innovation”.

Much of the college’s budget comes directly from the European Union, giving Google the opportunity to influence the thinking of future European politicians and regulators at an early stage in their careers.[92]

Google and Nesta Partner to Create British Think Tank

In addition to its academic support, Google expanded its European think-tank support as well, funding the creation of the Research Alliance for a Digital Europe (Readie) in 2015.[93] Managed by the London-based Nesta foundation, Readie’s stated mission is to collaborate directly with policymakers, industry experts, leading economists, and researchers to help European lawmakers craft digital policies.[94]

Unlike CEPS, which has a wide range of corporate supporters (described below), the Readie initiative appears to have only one: Google.[95]

Readie has published dozens of studies and articles on policy issues important to Google, such as artificial intelligence, digital policymaking, regulation and the future of work.[96] It has also hosted events aimed at European policymakers on digital policy and digital employment issues. Since its founding, Readie has hosted policy conferences with European policymakers in Stockholm, London, and Berlin.[97]

Google representatives are well represented at the events. For instance, a June 2016 “global webinar” sponsored by Readie included a conversation with Google economist Hal Varian, who explained that “big data actually creates jobs.”[98]

Varian also warned European policymakers against making policy too quickly. “It is a very rapidly moving system,” Varian noted. “You want to be careful about making decisions that lock you into certain policies too early.”

“You want to be careful about making decisions that lock you into certain policies too early.” Hal Varian

Google’s European lobbyists have also been frequent participants in Readie events, where they have rubbed shoulders with key European policymakers. Nicklas Lundblad, Google’s European lobbyist, was a presenter at Readie’s “Digital Done Better” policy summit in October 2016. The event brought together more than 100 ministers, state secretaries and elected representatives from 23 countries to discuss digital public policy in Europe.[99]

Lundblad’s presentation largely echoed Varian’s presentation extolling the benefits of big data on jobs and was delivered to an audience that included several high profile European policymakers, including German members of parliament and ministers of state, and the deputy prime minister of Slovenia.[100]

Readie’s Valerie Mocker pitches digital policy ideas to German chancellor Angela Merkel.

In September 2017, Google representatives Gustav Radell and Iarla Flynn presented to several ministers from Sweden and Estonia at a Readie-sponsored conference on “Digital skills and the future of work.”[101] Like Varian, Flynn noted that the organizational needs of the digital economy simply “change too rapidly for policy to keep up.”[102]

Readie representatives have also “pitched” their policy ideas directly to higher profile European leaders—including heads of state. Valerie Mocker, the current head of the Readie initiative, pitched her digital policy ideas directly to German chancellor Angela Merkel at a 2017 Women in Digital conference in Berlin.[103]

The meeting represented a key opportunity to lobby for policy issues important to Google, particularly given that German citizens were more skeptical about “digital innovation” than other Europeans, according to a Readie study.[104]

Google’s Funding for a Brussels Think Tank

In 2014, as Europe’s antitrust investigation of Google was gathering pace, the company became a corporate member of the Brussels-based Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS).[105] Widely recognized as one of Europe’s oldest and most influential think tanks, CEPS conducts research on a variety of policy issues before the European Commission and Parliament.

Neither Google nor CEPS have disclosed the size of Google’s donations since 2014.[106] However, Google appears to financially support CEPS and its scholars through multiple channels.

In addition to its annual corporate contribution, Google is also among a handful of corporate contributors to CEPS’ IdeasLab, an annual conference that brings together academics, think tanks and government leaders to discuss policy issues.[107] Google has sponsored the event every year since at least 2015, along with companies like Microsoft and Deloitte, and the European Commission.[108]

A CEPS scholar, Andrea Renda, was also the first beneficiary of a Google Chair endowed by the company at the College of Europe in Brussels.[109]

CEPS hosted a Google-sponsored event on privacy regulation in 2007 featuring many of the officials charged with regulating the matter. The conference, “Online Privacy: Reconsidering Policy Options for the Digital Age”, was attended by Europe’s Data Protection Supervisor, Peter Hustinx, and several other policymakers tasked with drafting regulations central to Google’s business. Google posted a video of the event on its corporate YouTube page.[110]

Following its donation to the think-tank in 2014, CEPS began to publish a series of policy papers that were sharply critical of the European Commission’s suit against Google. At the time, Google’s incipient settlement deal with the European Commission was falling apart amid accusations that it was too favorable to the search giant.[111] In November 2014, Europe’s new Competition Commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, took office as the European Parliament voted in symbolic move to break up Google.[112]

Two months later, CEPS scholars began to speak out in unison against the growing calls to regulate Google and other dominant internet firms, echoing Google’s arguments that the internet was simply too fluid to allow monopolies to become entrenched.

CEPS scholar and College of Europe “Google Chair” Andrea Renda

Andrea Renda, speaking at a panel before the European Parliament titled “Will Internet monopolies rule our economy in the 21st century?” opened his remarks by asking rhetorically, “What Internet monopolies?” [113] He downplayed concerns that technology giants would become entrenched, saying: “the Internet has been a constant cycle of winners and losers, where today’s winners are tomorrow’s losers.”[114]

European antitrust enforcement, Renda said, focused too much on traditional tests of market power. In Google’s case, he said, such market definitions may not apply. Echoing Google’s arguments, Renda further warned that resisting the advance of technology companies risked “degrading Europe’s competitiveness across the board” and raised the possibility of technology companies suggesting their own voluntary codes of conduct.

Renda did not disclose that Google had recently become a financial backer of CEPS.[115]

Three months later in April 2015, Renda released a paper titled “Antitrust, Regulation and the Neutrality Trap: A plea for a smart, evidence-based Internet policy.”[116] The paper argued that E.U. regulators should avoid extending the concept of net neutrality to search engines and online intermediaries such as Google. “Search neutrality and platform neutrality,” he wrote, “are fundamentally flawed principles that contradict the economics of the internet.”

Renda’s objection to “search neutrality” dovetailed neatly with Google’s interests at the time. The term had been central to the arguments made by Google’s critics about its market power.[117] The shopping comparison website Foundem, for example, had accused Google of illegally favoring its own search services over competitors in search results.[118] The complaint became the basis for much of the Commission’s antitrust inquiry.[119]

Renda’s paper mirrored the arguments put forth by the company and its defenders in the United States, some of whom have been funded by Google.[120]

Two months later, in June, Renda weighed in with a CEPS commentary titled “Antitrust on the ‘G string’: What’s behind the Commission’s investigations of Google and Gazprom?”[121] The inquiry, he wrote, was forcing the Competition Commission “into a complex and controversial probe, in which antitrust principles are likely to be stretched beyond their original scope.”

The inquiry, he wrote, was forcing the competition commission “into a complex and controversial probe, in which antitrust principles are likely to be stretched beyond their original scope.”

In September 2015, Renda published another paper critical of the Commission’s investigation of Google titled “Searching for harm or harming search? A look at the European Commission’s antitrust investigation against Google.”[122]

In it, Renda urged the Commission to “resist the temptation to imbue the antitrust case with an emphasis and meaning that have nothing to do with antitrust” and instead “devote its efforts to sharpening its understanding of dynamic competition in cyberspace.”

None of Renda’s papers disclosed Google’s financial support of CEPS.

The media also quoted his criticisms of the Europe’s probe into Google’s conduct. “We are using the manuals of competition law from the 1970s…and pretending we can impose old rules to this new setting,” Renda told Foreign Policy. [123] “This is going to weigh heavy on Europe’s ability to be a place you want to do business.”

The CEPS 2014 Annual Report reflected its increasingly skeptical tone toward potential action against U.S. technology companies:

Over the past months, EU institutions have repeatedly targeted online platforms as deserving heavy-handed regulation. GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple) are being criticised for avoiding taxes, breaching privacy, mishandling data, distorting competition and violating other users’ rights… Will the Old Continent shut the door to US-based IT giants, and if so, in the name of what ultimate policy goal?[124]

Renda’s Dual Roles

While working for CEPS, Renda also co-authored at least one official paper for the European Commission on a subject of intense interest to Google: “Does EU Regulation Hinder or Stimulate Innovation?”[125] The 2014 paper, which came as Google fought antitrust charges and privacy regulation in Europe, advocated for more flexible regulation, lower compliance costs and “red-tape burdens.”

It recommended that all future European legislation should include a test for potential harm to innovation.

The paper–written while he worked for CEPS but financed by the European Commission–raises questions about whether European regulators are formulating policy based on unbiased research. The paper did not disclose CEPS’s funding from Google.

In 2016, the company increased its backing of Renda, naming him the Google Chair in Digital Innovation at the College of Europe in Belgium.[126]

Almunia joins the CEPS board

Google’s contribution to CEPS in 2014 also came as the five year-term of EU Competition Commissioner Joaquin Almunia was ending. Almunia had taken a conciliatory approach in his antitrust case against Google, pursuing three settlement offers with the company and meeting personally with Google Chairman Eric Schmidt on several occasions to strike a deal.[127] Almunia ultimately abandoned his third and final attempt at a settlement after members of the European Parliament criticized him for not going far enough to rein in the company.[128]

Almunia’s successor, Margrethe Vestager, rekindled the Google investigation, increasing Google anxiety about its position in Europe and prompting the company to greatly step up its lobbying spending.[129]

In mid-2015, after Vestager formally charged the company for violating Europe’s antitrust rules, Almunia joined CEPS’s advisory board.[130] In November 2016, CEPS promoted Almunia to non-executive chairman of its board of directors.[131] Just six months out of office as Europe’s top competition regulator, Almunia would have inside information on the state of the cases against Google and the inner workings of the Commission.

During his 18-month “cooling off period,” Almunia largely avoided matters concerning Google. Since becoming CEPS’ chairman, however, he has participated in at least one event that would have been of interest to Google.

In December 2017, Almunia offered a progress report on digital initiatives at a CEPS event entitled “A Digital Presidency: Takeaways from Estonia’s Programme for a Digital Europe.”[132] The event covered several policy issues important to Google including copyright reform, the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation (a key component of which were new “right to be forgotten” rules), and the EU’s digital single market and digital taxes.[133]

Google and companies it has started, like Sidewalk Labs, view Estonia as a model for digital services that other countries should emulate. [134] When Estonia was appointed to lead the Council of the European Union for the first time in the second half of 2017, it called for the “free movement of data” and the creation of the Digital Single Market as the country’s top priorities. Both were key policy issues for Google.[135]

Sharing the podium with Almunia were Estonian Prime Minister Jüri Ratas and Andrus Ansip, the European Commissioner for the Digital Single Market. Ansip, a former prime minister of Estonia, has been described as “the most powerful person in Europe today” on digital policy.[136] Ansip oversaw the drafting of the digital single market rules, including provisions limiting an EU member country’s ability to demand that data be stored on servers within its borders–a provision that Google and other technology companies also support.[137]

Google’s Chief Legal Officer David Drummond remarked in a 2015 Brussels speech that “the biggest step the EU can make is to complete the formation of the digital single market” which he described as critical to the continent’s growth.[138]

Google Policy Manager William Echikson Joins CEPS

In February 2017, CEPS hired a Google policy manager, William Echikson.[139] Echikson now heads the organization’s digital forum, described as a “multi-stakeholder platform aimed at raising the level of debate about the policy challenges that arise from the European Commission’s Digital Single Market strategy.”[140]

Former Google lobbyist and CEPS digital forum head Bill Echikson

During his time at Google, Echikson had worked on several key policy issues for the company, including the fight over Google Books, antitrust issues faced by the company in France and Italy and the regulatory battle over the “right to be forgotten”—an E.U. guideline, opposed by Google, that allows users to request the removal of personal information from the web.[141]

Since joining CEPS, Echikson has written articles and given presentations taking positions that closely align with Google’s. In April 2017, for example, he argued in an op-ed that Europe should not jettison the legal immunity enjoyed by technology companies for crimes committed using their platforms. [142]

The article noted his CEPS affiliation and even his work as a former journalist. However, it made no mention of his six-year stint at Google—despite the fact that the subject was a key policy priority for his former employer.[143]

Pitching Jobs

At a time when technology companies are under fire in Europe, Echikson has also argued that “the internet is creating far more jobs than it is destroying – and that many of these jobs are being created in traditional industrial areas.”

Those Google-friendly arguments have reached an influential audience. On November 7, 2017, CEPS invited officials from the European Commission and the European Committee of Regions — the EU’s assembly of local and regional representatives — to a full-day event titled “Internet of opportunity: Will the Internet benefit all Europeans?”[144]

“The answers were, overall, optimistic,” the organizers wrote.

The event featured presentations by Echikson and Google vice president Vint Cerf, who joined the gathering by video. Echikson presented his paper “The Internet and Jobs: A Giant Opportunity for Europe” to the assembly of officials, arguing that the internet is an engine for creating more jobs. [145]

“Europe is entering the new digital era paralyzed by fear that it will destroy jobs. Instead, it should see the possibility of new positive horizons. Policymakers must take a deep breath and calm down,” Echikson wrote.

In effect, the paper served as a defense of Google’s job creation in Europe, which could be threatened by unfavorable tax treatment of technology companies. Ten days before the CEPS event, the European Commission announced it was contemplating imposing new taxes on companies with a digital presence in Europe as well as a new “unitary tax” to be levied on a share of tech companies’ global profits.[146]

“Policymakers must take a deep breath and calm down,” Echikson wrote.

Google and the European Commission Co-Finance Studies

In some cases, Google and the European Commission have jointly funded studies supporting the company’s views. For example, Lilian Edwards, who serves on the editorial board of the IPR, co-authored a study with Ian Hargreaves and several other intellectual property experts entitled “Intellectual Property and Innovation.”[147]

Produced by the Brussels-based Lisbon Council, the study thanked Google and the European Commission’s Education, Audiovisual and Cultural Executive Agency for co-funding the research, including a disclosure noting, “with the support of the European Union.”[148]

Hargreaves, a journalist and professor of digital economy at Cardiff University in Wales, was appointed by UK Prime Minister David Cameron in 2010 to oversee the UK’s copyright consultation known as the “Hargreaves Review into IP Growth.”[149] Criticized by supporters of strong copyright laws as the “Google Review,” the Hargreaves Review urged the U.K. Government to update copyright rules by exempting text and data mining from copyright restrictions. It also called for allowing exceptions for private copying and parody of copyrighted material, measures that Google has also supported.[150]

The text and data mining exemption was particularly important as European laws were presenting unique challenges for Google Books. The rules limited the company’s scans to works held by its library partners in the public domain and books for which it had negotiated scanning rights with the copyright-holders.[151]

Edwards and Hargreaves presented the paper at an October 2012 Lisbon Council Summit on innovation chaired by Neelie Kroes, the vice president of the European Commission in charge of the digital agenda.[152]

Footnotes

[1] https://campaignforaccountability.org/new-report-reveals-googles-extensive-financial-support-for-academia/; Brody Mullins and Jack Nicas, Paying Professors: Inside Google’s Academic Influence Campaign, The Wall Street Journal, July 14, 2017, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/paying-professors-inside-googles-academic-influence-campaign-1499785286.

[2] https://www.hiig.de/en/financing/.

[3] Google Becoming “Giant Monopoly” -German Minister, Reuters, January 11, 2010, available at https://uk.reuters.com/article/idUKLDE60809T20100109?sp=true; Google Slammed With Antitrust Complaints in Germany, Reuters, January 19, 2010, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/urnidgns852573c400693880002576b00039190c/google-slammed-with-antitrust-complaints-in-germany-idUS291704123820100119.

[4] https://www.hiig.de/en/publications/; See e.g. Malte Ziewitz, Can Crowd Wisdom solve Regulatory Problems, Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society, 1st Berlin Symposium

on Internet and Society, October 2011, available at https://www.hiig.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/crowdregulation_0.pdf; Pype, Daalderop, et. al., Privacy and Security in Autonomous Vehicles, Automated Driving: Safer and More Efficient Future Driving (Book), 2017, available at https://www.hiig.de/publication/automated-driving-safer-and-more-efficient-future-driving/; H. Maier, Digital Copyright & Free Speech: Technische Schutznahmen nach US-Recht auf dem Prüfstand, Telemedicus, 2016, available at https://www.hiig.de/publication/digital-copyright-free-speech-technische-schutznahmen-nach-us-recht-auf-dem-pruefstand/.

[5] https://policyreview.info/about.

[6] http://networkofcenters.net/centers.

[7] Id.; http://networkofcenters.net/about.

[8] https://readie.eu/about-us/; https://readie.eu/news-and-opinion/; https://readie.eu/events/.

[9] 2012 Annual Report, Internet and Society Collaboratory, April 2013, page 25, available at https://issuu.com/collaboratory/docs/collaboratoryjahresbericht2012; https://web.archive.org/web/20170710065716/http://www.net-lab.fr/p/netlab.html.

[10] https://www.uw.edu.pl/uniwersytet/wydzialy-i-jednostki/jednostki-naukowe-i-dydaktyczne/digital-economy-lab/.

[11] Ian Hargreaves and Paul Hofheinz, Intellectual Property and Innovation, Lisbon Council Policy Brief, Vol. VI, No. 2 (2012), available at https://orca.cf.ac.uk/38248/1/4_lisboncouncilfinalipdoc.pdf.

[12] Jacques Pelkmans and Andrea Renda, Does EU Regulation Hinder or Stimulate Innovation?, CEPS Special Report, November 2014, page 1, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2528409.

[13] Commission Staff Working Document, Better Regulations for Innovation-Driven Investment at the EU Level, European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, 2016, fn. 3, available at https://ec.europa.eu/research/innovation-union/pdf/innovrefit_staff_working_document.pdf.

[14] Mullins and Nicas, Wall Street Journal, Jul. 14, 2017, Kenneth P. Vogel, Google Critic Ousted From Think Tank Funded by the Tech Giant, The New York Times, August 30, 2017, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/30/us/politics/eric-schmidt-google-new-america.html.

[15] Thinking Allowed?, How Think Tanks Facilitate Corporate Lobbying, Corporate Europe Observatory, July 5, 2016, available at https://corporateeurope.org/power-lobbies/2016/07/thinking-allowed; Rowland Manthorpe, Google Could be Fined $1bn by the European Commission as its Antitrust Case Comes to an End, Wired, June 16, 2017, available at http://www.wired.co.uk/article/timeline-googles-marathon-anti-trust-case-with-the-eu.

[16] Nicolai van Gorp, Cross-Competition Among Information (Digital) Platforms, Directorate General for Internal Policies, January 20, 2015, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/542187/IPOL_STU(2015)542187_EN.pdf; Andrea Renda, Antitrust, Regulation and the Neutrality Trap: A Plea for a Smart, Evidence-based Internet Policy, CEPS Special Report, April 2015, available at https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/SR104_AR_NetNeutrality.pdf.

[17] http://www.searchneutrality.org/topic/search-neutrality.

[18] CEPS then appointed Joaquin Almunia, Europe’s former competition commissioner, as chairman. Almunia had built a rapport with Google during his repeated efforts to settle the case on terms that critics said were too favorable to the company, hashed out at a meeting with Google’s Eric Schmidt at Davos. Almunia was viewed as far more sympathetic to Google’s arguments than his successor in the post, who has pursued several antitrust suits against the company. See Claire Cain Miller and Mark Scott, Google Settles Its European Antitrust Case; Critics Remain, The New York Times, February 5, 2014, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/06/technology/google-reaches-tentative-antitrust-settlement-with-european-union.html; Christian Oliver, EU Competition Commissioner Breaks with Her Predecessor’s Practices, Financial Times, April 15, 2015, available at https://www.ft.com/content/2982f3b8-e379-11e4-aa97-00144feab7de.

[19] https://www.ceps.eu/profiles/william-echikson; William Echikson, The Internet and Jobs, A Giant Opportunity for Europe, CEPS Policy Insights, November 1, 2017, available at https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/PI2017-38InternetAndJobs.pdf.

[20] Id.; The European Committee of the Regions and the Estonian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, European committee on the Regions, September 2017, available at https://cor.europa.eu/en/documentation/brochures/Documents/The%20European%20Committee%20of%20the%20Regions%20and%20the%20Estonian%20Presidency%20of%20the%20Council%20of%20the%20European%20Union/3210_Broch_ET%20Presdcy_EN_web.pdf.

[21] Michael Birnbaum and Brian Fung, E.U. fines Google a Record $2.7 Billion in Antitrust Case Over Search Results, The Washington Post, June 27, 2017, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/eu-announces-record-27-billion-antitrust-fine-on-google-over-search-results/2017/06/27/1f7c475e-5b20-11e7-8e2f-ef443171f6bd_story.html; Mark Scott, Europe Approves Tough New Data Protection Rules, The New York Times, December 15, 2015, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/16/technology/eu-data-privacy.html.

[22] Press Release, Google Inc. Pledges $2M to Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society, Stanford Center for Internet and Society, November 28, 2006, available at https://law.stanford.edu/press/google-inc-pledges-2m-to-stanford-law-school-center-for-internet-and-society/.

[23] John Hechinger and Rebecca Buckman, The Golden Touch of Stanford’s President, The Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2007, available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB117226912853917727.

[24] Eric Schmidt, Google in Europe: Innovations for a Digital Future, Walter Hallstein-Institut für Europäisches Verfassungsrecht, February 16, 2011, available at https://www.rewi.hu-berlin.de/de/lf/oe/whi/FCE/archiv/rede-schmidtii.pdf.

[25] https://web.archive.org/web/20110924082035/http://www.berlinsymposium.org:80/; Max Senges, Launching an Internet & Society Research Institute, Google Europe Blog, October 24, 2011, available at

[26] https://www.hiig.de/en/events/berlin-symposium-on-internet-and-society/.

[27] https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=483&v=ggmHz73Z7uU.

[28] Senges, Google Europe Blog, Oct. 24, 2011.

[29] Eric Pfanner, In Europe, Challenges for Google, The New York Times, February 1, 2010, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/02/technology/companies/02google.html.

[30] Jemima Kiss, Google Launches ‘Advisory Council’ Page on Right to be Forgotten, The Guardian, July 11, 2014, available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jul/11/google-advisory-council-page-right-to-be-forgotten.

[31] Kevin J. O’Brien, Google Data Admission Angers European Officials, The New York Times, May 15, 2010, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/16/technology/16google.html; Cyrus Farivar, Germany Fines Google a Paltry $189,000 over Street View Wi-Fi Scanning, Ars Technica, April 22, 2013, available at https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2013/04/germany-fines-google-a-paltry-189000-over-street-view-wi-fi-scanning/.

[32] Google Slammed With Antitrust Complaints in Germany, Reuters, January 19, 2010, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/urnidgns852573c400693880002576b00039190c/google-slammed-with-antitrust-complaints-in-germany-idUS291704123820100119.

[33] Senges, Google Europe Blog, Oct. 24, 2011.

[34] https://www.hiig.de/en/financing/.

[35] Id.

[36] https://www.hiig.de/en/people/?view=directors#staff-directors; Regina Friedrich, Towards a Digital Future, Goethe Institut, February 2012, available at https://www.goethe.de/en/kul/med/20367560.html.

[37] Id.

[38] https://web.archive.org/web/20180207210948/http://www.stiftung-internet-und-gesellschaft.de/en/support/.

[39] https://www.linkedin.com/in/wieland-holfelder-2171bb/?locale=de_DE; http://internet-society-foundation.com/en/committees/.

[40] Id.

[41] https://www.hiig.de/en/blog/the-internet-and-human-rights-reviews/.

[42] Sven Becker, Internet Giant Builds Web of Influence in Berlin, Der Spiegel, September 25, 2012, available at http://www.spiegel.de/international/business/how-google-lobbies-german-government-over-internet-regulation-a-857654-2.html.

[43] Id.

[44] Press Release, Foreign Minister Westerwelle to Host a Conference on the Internet and Human Rights, German Federal Foreign Office, available at https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/Newsroom/120912-konf-internet-u-menschenrechte/251456.

[45] https://www.linkedin.com/in/jessica-schmeiss-b477b016/?locale=en_US.

[46] https://www.linkedin.com/in/enginbozdag/; https://www.hiig.de/en/staff/tiffany-quach/.

[47] https://www.linkedin.com/in/maxsenges/.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] https://www.hiig.de/en/eventslist/; https://www.hiig.de/en/publications/.

[51] https://www.hiig.de/en/events/cloud-computing-and-eu-data-protection-regulation-2/; https://www.hiig.de/en/events/the-future-of-privacy-governance/; https://www.hiig.de/en/events/beyond-online-copyright-enforcement-lunch-talk-with-sharon-bar-ziv/.

[52] https://web.archive.org/web/20130607223155/http://policyreview.info:80/about.

[53] https://www.strath.ac.uk/staff/edwardslilianprof/.

[54] Press Release, Professor Maurizio Borghi Receives Google Research Award, Bournemouth University, October 3, 2014, available at https://www1.bournemouth.ac.uk/news/2014-10-03/professor-maurizio-borghi-receives-google-research-award.

[55] https://research.google.com/research-outreach.html#/research-outreach/faculty-engagement/faculty-research-award-recipients.

[56] https://americanassembly.org/people/staff/joe-karaganis.

[57] Joe Karaganis and Lennart Renkema, Copy Culture in the US & Germany, The American Assembly, 2013, available at https://americanassembly.org/publications/copy-culture-us-and-germany; Jennifer M. Urban, Joe Karaganis, and Brianna Schofield, Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, UC Berkeley Public Law Research Paper, March 24 2017, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2755628.

[58] https://nexa.polito.it/people/fmorando.

[59] Note: After publication, Nexa contacted CfA to clarify that it has received €175,496.60 from Google; See also https://nexa.polito.it/transparency-and-accountability; Vogel, The New York Times, Aug. 30, 2017.

[60] https://policyreview.info/users/daphne-keller.

[61] https://www.linkedin.com/in/ahkyee/; Andy Yee, The Regulation of Cryptocurrencies: from Disintermediation to Reintermediation, Internet Policy Review, January 14, 2015, available at https://policyreview.info/articles/news/regulation-cryptocurrencies-disintermediation-reintermediation/350.

[62] https://policyreview.info/articles/news/intermediaries-and-free-expression-under-gdpr-brief/388 and https://nexa.polito.it/nexacenterfiles/Nexa-Center-annual_report-2013.pdf

[63] Press Release, Google to Invest in Science “Made in German”, Technical University of Berlin, February 2, 2018, available at https://www.tum.de/en/about-tum/news/press-releases/detail/article/34489/.

[64] Wieland Holfelder, Celebrating the Fifth Anniversary of the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society, Google in Europe, October 5, 2016, available at https://blog.google/topics/google-europe/celebrating-fifth-anniversary-humboldt-institute-internet-and-society/.

[65] Sebastian Haselbeck, Co:Lab sucht Verstärkung im Vorstand, Internet und Gesellschaft Collaboratory Blog, March 7, 2013, available at http://blog.collaboratory.de/colab-sucht-verstaerkung-im-vorstand/; Tobias Schwartz, Da geht was – strukturelle und personelle Veränderungen im Co:Lab, Internet und Gesellschaft Collaboratory Blog, April 30, 2014, available at http://blog.collaboratory.de/da-geht-was-strukturelle-und-personelle-veraenderungen-im-colab/; https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&u=http://blog.collaboratory.de/&prev=search.

[66] https://www.telemedicus.info/soko16/.

[67] Jahresbericht 2012, Internet und Gesellschaft Collaboratory, April 2013, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20160826120653/http://dl.collaboratory.de/CollaboratoryJahresbericht2012.pdf.

[68] Resa Mohabbat Kar, Digitale Denkfabrik Collaboratory stellt Arbeit ein, Internet und Gesellschaft Collaboratory Blog, March 19, 2017, available at http://blog.collaboratory.de/digitale-denkfabrik-collaboratory-stellt-arbeit-ein/.

[69] 2012 Annual Report, Internet and Society Collaboratory, April 2013, page 25. available at https://issuu.com/collaboratory/docs/collaboratoryjahresbericht2012; https://web.archive.org/web/20170710065716/http://www.net-lab.fr/p/netlab.html.

[70] 2012 Annual Report, Internet and Society Collaboratory, April 2013, page 25. available at https://issuu.com/collaboratory/docs/collaboratoryjahresbericht2012; https://web.archive.org/web/20170710065716/http://www.net-lab.fr/p/netlab.html.

[71] https://web.archive.org/web/20170313224317/http://www.net-lab.fr/p/netlab.html.

[72] https://web.archive.org/web/20170313164231/http://www.net-lab.fr/p/qui-sommes-nous.html.

[73] https://www.linkedin.com/in/cedricmanara; Cedric Manara, Attacking the Money Supply to Fight Against Online Illegal Content?, EDHEC Business School Research Centre, September 2012, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2177835.

[74] Cedrick Manara, Curriculum Vitae, available at http://www.cedricmanara.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/cv_cedric_manara.pdf.

[75] https://www.uw.edu.pl/uniwersytet/wydzialy-i-jednostki/jednostki-naukowe-i-dydaktyczne/digital-economy-lab/.

[76] http://www.delab.uw.edu.pl/en/portfolio-items/katarzyna-sledziewska/?portfolioCats=677.

[77] Id.; https://readie.eu/about-us/.

[78] Press Release, The Google@HEC Chair is Launched, HEC Paris/Google, January 30, 2012, available at http://www.hec.edu/var/fre/storage/original/application/eda4445e9af7947681396d5c3c81c972.pdf.

[79] http://www.hec.edu/Corporate-Partnerships/Corporate-partners-of-the-HEC-Foundation.

[80] http://www.cpdpconferences.org/conferencepartners.html.

[81] Bárbara Navarro, Cátedra Google “Privacidad, Sociedad e Innovación” de la Universidad CEU San Pablo, Google Blog Official de Google España, June 21, 2012, available at https://espana.googleblog.com/2012/06/catedra-google-privacidad-sociedad-e.html.

[82] The Man Who Sued Google to be Forgotten, Reuters, May 30, 2014, available at http://www.newsweek.com/man-who-sued-google-be-forgotten-252854.

[83] Aoife White and Gaspard Sebag, Google Fight on Right to Be Forgotten Is EU Case of Déjà vu, Bloomberg, July 19, 2017, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-19/google-s-french-battle-on-right-to-be-forgotten-goes-to-eu-court.

[84] https://archive.google.com/advisorycouncil/.

[85] Jose Luis Pinar Manas, ‘Caso Google’: ¿una mejor privacidad?, El Pais, May 15, 2014, available at https://elpais.com/elpais/2014/05/14/opinion/1400086304_243572.html.

[86] http://www.uspceu.com/prensa/archivos/AGE26062017125606156.pdf.

[87] https://www.coleurope.eu/news/google-chair-digital-innovation.

[88] https://www.coleurope.eu/news/new-google-chair-digital-innovation; https://www.linkedin.com/in/lie-junius-b4b01b19; https://www.goodyear.eu/corporate/it/our-company/leadership/lie-junius.jsp.

[89] https://www.coleurope.eu/study/european-economic-studies/google-chair-digital-innovation.

[90] Id. https://www.coleurope.eu/whoswho/person/andrea.renda.

[91] Kristiano Ang, School of the E.U. Elite Adapts to a Changing Climate, The New York Times, August 3, 2014, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/04/world/europe/college-of-europe-aims-to-produce-well-rounded-civil-servants.html.

[92] Id.

[93] Site Lookup, Domaintools.com.

[94] https://readie.eu/what-we-do/.

[95] https://readie.eu/about-us/.

[96] https://readie.eu/news-and-opinion/.

[97] https://readie.eu/events/.

[98] https://readie.eu/opinion/in-conversation-with-hal-varian/.

[99] https://se.linkedin.com/in/nicklas-berild-lundblad-29aa1; https://readie.eu/news/readie-policy-summit-2016-digital-done-better/.

[100] Id.

[101] https://readie.eu/events/digital-skills-and-the-future-of-work-stockholm/.

[102] https://readie.eu/news/updating-digital-skills-how-can-companies-individuals-and-policymakers-prepare-for-the-future-of-work-2/.

[103] Felix Rentsch, Policy Adviser Reveals the Advice She Has Given Merkel for Digitization, Business Insider, July 28, 2017, (German translation) available at https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&u=http://www.businessinsider.de/politikberaterin-valerie-mocker-im-interview-ueber-digitalisierung-2017-7&prev=search.

[104] https://www.nesta.org.uk/publications/digital-pulse-how-ready-are-germans-digital-life.

[105] A review of CEPS’ annual reports does not list Google as a financial supporter until 2014. The amount of Google’s contribution to the think tank is not disclosed. See https://www.ceps.eu/content/ceps-highlights.

[106] Id.

[107] https://www.ceps.eu/content/ceps-ideas-lab; Programme, 2017 CEPS Ideas Lab, available at https://www.ceps.eu/sites/default/files/ProgrammeIdeasLab2017.pdf.

[108] Id.; Programme, 2016 CEPS Ideas Lab, available at https://www.ceps.eu/sites/default/files/CEPSIdeasLab2016.pdf; Programme, 2015 CEPS Ideas Lab, available at https://www.ceps.eu/sites/default/files/Programme%20%20CEPS%20IdeasLab%202015.pdf.

[109] https://www.coleurope.eu/news/new-google-chair-digital-innovation.

[110] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZbacAnB1nU.

[111] Google’s EU Antitrust Deal Falls Apart, Associated Press, September 9, 2014, available at https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/09/09/googles-eu-antitrust-deal-falls-apart/.

[112] James Kanter, E.U. Parliament Passes Measure to Break Up Google in Symbolic Vote, The New York Times, November 27, 2014, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/28/business/international/google-european-union.html.

[113] van Gorp, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Jan. 20, 2015.

[114] Id.

[115] Id.

[116] Renda, CEPS Special Report, Apr. 2015.

[117] Adam Raff, Search, but You May Not Find, The New York Times, December 27, 2009, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/28/opinion/28raff.html.

[118] Charles Duhigg, The Case Against Google, The New York Times, February 20, 2018, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/20/magazine/the-case-against-google.html.

[119] Id.; http://www.searchneutrality.org/.

[120] Marvin Ammori and Luke Pelican, Proposed Remedies for Search Bias, “Search Neutrality” and Other Proposals in the Google Inquiry, Journal of Internet Law, May 14, 2012, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2058159; Geoffrey A. Manne and Joshua Wright, If Search Neutrality is the Answer, What’s the Question?, ICLE Antitrust & Consumer Protection Program White Paper Series, 2011, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1807951.

[121] Andrea Renda, Antitrust on the ‘G string’, What’s Behind the Commission’s Investigations of Google and Gazprom?, CEPS Commentary, June 15, 2015, available at https://www.ceps.eu/publications/antitrust-%E2%80%98g-string%E2%80%99-what%E2%80%99s-behind-commission%E2%80%99s-investigations-google-and-gazprom.

[122] Andrea Renda, Searching for Harm or Harming Search?, A Look at the European Commission’s Antitrust Investigation Against Google, CEPS Special Report, September 2015, available at https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/AR%20Antitrust%20Investigation%20Google.pdf.

[123] Suzy Hansen, Meet the Woman Leading Europe’s War Against Google, Gazprom, and Apple, Foreign Policy, March 18, 2016, available at http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/18/the-face-of-justice-margrethe-vestager-eu-google-gazprom-antitrust/.

[124] Highlights 2014-2015, Centre for European Policy Studies, page 11, available at https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/CEPS%20highlights%202014-15_0.pdf.

[125] Pelkmans and Renda, CEPS Special Report, Nov. 2014.

[126] https://www.coleurope.eu/study/european-economic-studies/google-chair-digital-innovation; https://www.coleurope.eu/news/google-chair-digital-innovation.

[127] Charles Author, Google Antitrust Inquiry: Eric Schmidt Meets Europe’s Competition Chief, The Guardian, December 5, 2011, available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/dec/05/google-antitrust-inquiry-eric-schmidt; Brad Stone and Vernon Silver, Google’s $6 Billion Miscalculation on the EU, Bloomberg Businessweek, August 5, 2015, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2015-08-06/google-s-6-billion-miscalculation-on-the-eu.

[128] Nicholas Hirst, Almunia Struggles to Defend Google Case, Politico, September 24, 2014, available at https://www.politico.eu/article/almunia-struggles-to-defend-google-case/.

[129] James Kanter, E.U. Antitrust Enforcer Will Be Margrethe Vestager, The New York Times, September 10, 2014, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/11/business/international/eu-antitrust-enforcer-will-be-margrethe-vestager.html; Ivana Kottasova, Google is spending millions more to lobby Europe, CNN, September 29, 2015, available at http://money.cnn.com/2015/09/29/technology/google-europe-lobbying/index.html.

[130] Klint Finley, EU Formally Accuses Google of Antitrust Violations, Wired, April 15, 2015, available at https://www.wired.com/2015/04/eu-google/; https://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/2172/response/7705/attach/2/Annexes.pdf.

[131] Press Release, Joaquin Almunia elected Chairman of the CEPS Board of Directors, Centre for Euroepan Policy Studies, November 29, 2016, available at https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/PRAlmuniaChairCEPS28112016.docx.

[132] A Digital Presidency. Takeaways from Estonia’s Programme for a Digital Europe, Centre for European Policy Studies, December 14, 2017, available at https://www.ceps.eu/events/digital-presidency-takeaways-estonias-programme-digital-europe.

[133] https://www.parlementairemonitor.nl/9353000/1/j9tvgajcovz8izf_j9vvij5epmj1ey0/vkgcu3yt0eri?ctx= vhyzn0vt5cvu&tab=1&start_tab1=30.

[134] Steve Lohr, Sidewalk Labs, a Start-Up Created by Google, Has Bold Aims to Improve City Living, The New York Times, June 10, 2015, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/11/technology/sidewalk-labs-a-start-up-created-by-google-has-bold-aims-to-improve-city-living.html; https://www.sidewalklabs.com/blog/how-estonia-became-a-global-model-for-e-government/.

[135] Joshua Bleiberg and Darrell M. West, The Benefits of a Digital Single Market in Europe and the United States, Brookings, June 17, 2015, available at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2015/06/17/the-benefits-of-a-digital-single-market-in-europe-and-the-united-states/.

[136] Leo Mirani, Europe Wants to be the World’s Leading Tech Power. Andrus Ansip is Tasked with Making it Happen, Quartz, August 3, 2015, available at https://qz.com/457111/europe-wants-to-be-the-worlds-leading-tech-power-andrus-ansip-is-tasked-with-making-it-happen/.

[137] https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/european-innovation-focus-vice-president-ansip-and-belgian-deputy-prime-minister-de-croo-visit; George Lynch, EU Governments to Negotiate With Parliament Over Digital Economy Data Transfer Law, Bloomberg BNA, January 4, 2018, available at https://www.bna.com/eu-governments-negotiate-b73014473803/.

[138] David Drummond, Google: Entrepreneurial Spirit in the Digital Single Market, Lisbon Council, 2015, available at https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/content/google-entrepreneurial-spirit-digital-single-market.

[139] https://www.linkedin.com/in/billechikson/.

[140] Id.; https://www.ceps.eu/content/ceps-digital-forum.

[141] https://www.linkedin.com/in/billechikson/; https://www.ceps.eu/content/william-echikson.

[142] William Echikson, Limited Liability for the Net? The Future of Europe’s E-Commerce Directive, Huffington Post, April 13, 2017, available at https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/58ecd2cfe4b0145a227cb846.

[143] Internet Firms’ Legal Immunity is Under Threat, Economist, February 11, 2017, available at https://www.economist.com/news/business/21716661-platforms-have-benefited-greatly-special-legal-and-regulatory-treatment-internet-firms.

[144] https://www.ceps.eu/content/internet-opportunity-will-internet-benefit-all-europeans.

[145] Id.; William Echikson, The Internet and Jobs, A Giant Opportunity for Europe, CEPS Policy Insights, November 1, 2017, available at https://www.ceps.eu/publications/internet-and-jobs-giant-opportunity-europe.

[146] Francesco Guarascio, EU Considers Tax on Digital Firms’ Global Profits, Reuters, October 26, 2017, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-tax-digital/eu-considers-tax-on-digital-firms-global-profits-idUSKBN1CV2OB.

[147] Ian Hargreaves and Paul Hofheins, Editors, Intellectual Property and Innovation, The Lisbon Council, September 10, 2012, available at http://www.lisboncouncil.net/publication/publication/84-intellectual-property-and-innovation-a-framework-for-21st-century-growth-and-jobs-.html.

[148] Id.

[149] Press Release Ian Hargreaves to Lead Independent Review into IP and Growth, Department for Business, November 10, 2010, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ian-hargreaves-to-lead-independent-review-into-ip-and-growth; https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/people/view/182934-hargreaves-ian.

[150] Andrew Orlowski, The Google Review: Now Speak Your Brains, The Register, December 16, 2011, available at https://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/12/16/hargreaves_ip_consultation/; Press Release, New Exceptions to Copyright Reflect Digital Age, Intellectual Property Office, June 1, 2014, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-exceptions-to-copyright-reflect-digital-age.

[151] Tom Krazit, European Laws Present Challenges for Google Books, CNET, October 23, 2009, available at https://www.cnet.com/uk/news/european-laws-present-challenges-for-google-books/.

[152] http://www.lisboncouncil.net/news-a-events/403-vice-president-kroes-keynotes-intellectual-property-.