Academic for Hire

On February 25, 2019, CfA released a new report, Academic for Hire, revealing that a lawyer for the payday lending industry, Hilary Miller, funded, designed, and edited an academic study defending the payday lending industry. Mr. Miller, the chairman of the Consumer Credit Research Foundation worked closely with Kennesaw State University Professor Jennifer Priestley to develop a study for the payday lending industry to use to lobby against government regulations that would have protected consumers from payday lenders.

Click here to download a PDF copy of the report.

Executive Summary

Payday lenders have paid academics repeatedly to write favorable articles about their industry. Campaign for Accountability’s (CfA) new report, Academic for Hire, relying on documents obtained through a public records request, reveals that in one case, a payday lending lawyer funded, edited, and disseminated an academic study defending his clients’ business model. He then stamped a compliant professor’s name on the paper, which allowed the industry to use it to lobby against government regulations curtailing the industry’s predatory practices.

In 2015, CfA asked Kennesaw State University (KSU) in Georgia to release all communications between a payday lending lawyer, Hilary Miller, and a KSU professor, Jennifer Priestley, Ph.D. In December 2014, Dr. Priestley had published a paper defending the payday lending industry. Dr. Priestley wrote in in a footnote that she had received funding from the payday lending industry, but she claimed the industry did not exercise any control over the production of the paper.

After a three-year lawsuit, CfA obtained the communications between Dr. Priestley and Mr. Miller.[1] The emails reveal in startling detail how Mr. Miller managed the entire production of Dr. Priestley’s paper from writing the abstract to supervising the release. Mr. Miller, for instance, rewrote entire drafts of Dr. Priestley’s paper without tracking his changes. He repeatedly implored her to add references to other papers he had funded, and he solicited comments from CCRF-funded academics to improve Dr. Priestley’s paper. In response to one of Mr. Miller’s suggested edits, Dr. Priestley wrote, “I am here to serve.”

This report documents the back and forth between Mr. Miller and Dr. Priestley, which allowed Mr. Miller to produce a sophisticated defense of the payday lending industry using Dr. Priestley’s name. The report also details how payday lenders use studies like Dr. Priestley’s paper to lobby against federal regulations that protect consumers from the industry.

Introduction

In 2010, Congress passed the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).[2]Congress gave the CFPB jurisdiction to regulate, among other things, payday loans. These short-term loans, usually worth a few hundred dollars, carry an extremely high interest rate and require borrowers to repay them within a few days or weeks.[3]Due to the high interest rates and quick repayment periods, customers are often trapped in a cycle of debt where they must take out new loans to pay back the old ones. Each year, the industry provides loans to about 12 million Americans who spend about $9 billion on fees.[4]

Consumer protection advocates have long believed that payday lenders unfairly prey on low-income consumers. For years, they have lobbied Congress and state legislatures to rein in the industry.[5]With the passage of Dodd Frank, consumer advocates hoped the federal government would enact regulations to curb the worst abuses of payday lenders.

Facing the threat of an empowered CFPB, the payday lending industry recruited academics to write favorable studies to thwart the agency’s agenda. While many industries pay social scientists to produce supportive articles, the emails obtained by CfA demonstrate that a payday lending lawyer, Hilary Miller, went far beyond the normal course of business. In short, Mr. Miller served as the industry’s academic-in-residence, recruiting pliant professors and ghostwriting obsequious studies.

In 2011, for example, former Arkansas Tech University Professor Marc Fusaro, Ph.D., and a for-profit researcher, Patricia Cirillo, Ph.D., ostensibly published a paper about payday loans entitled Do Payday Loans Trap Consumers in a Cycle of Debt?[6]In 2015, CfA released a report revealing the paper was supervised and edited by Mr. Miller, who is the chairman of the Consumer Credit Research Foundation (CCRF), a nonprofit group funded by the payday lending industry.[7]Mr. Miller, who is also the chairman of the Short-Term Loan Bar Association, wrote entire sections of the paper and implemented a press strategy to bring it “to the attention of the national press and policymakers.”[8]

More recently, CCRF funded Dr. Priestley’s paper, entitled Payday Loan Rollovers and Consumer Welfare.[9]Published in December 2014, it reads like a defense of the payday lending industry.[10]The abstract states, “borrowers who engage in protracted refinancing (‘rollover’) activity have better financial outcomes (measured by changes in credit scores) than consumers whose borrowing is limited to shorter periods” and “consumers whose borrowing is less restricted by regulation fare better than consumers in the most restrictive states.”[11]That language, which argues that payday loan rollovers are a benefit to consumers, was lifted nearly verbatim from what Mr. Miller had drafted and sent to Dr. Priestley 11 months earlier.[12]

Despite Mr. Miller’s leading role in drafting the paper, it contains this false disclaimer:

This research was supported by a grant from Consumer Credit Research Foundation. The Foundation did not exercise any control over the methodology or analysis used in this study or over the editorial content of this paper.[13]

In June 2015, CfA filed an open records request with KSU to investigate the claim that CCRF played no role in crafting the paper.[14]CfA asked the university to release all communications between Dr. Priestley and Mr. Miller.[15]KSU agreed to release the documents, but CCRF filed a lawsuit against KSU to prohibit the university from delivering the records.[16]CfA moved to intervene in the lawsuit and for three years fought to obtain the records. Only after the Georgia Supreme Court ruled in CfA’s favor was KSU allowed to release the documents.[17]

The documents reveal in scandalous detail why CCRF fought to prevent them from being released. Mr. Miller designed, edited, and distributed Dr. Priestley’s paper to counteract the CFPB’s efforts to rein in the abuses in the payday lending industry.

Miller’s Communications with Priestley

Hilary Miller is the sole individual involved in CCRF, which exists only to fund academic papers that highlight the payday lending industry.[18]In his role as the chair of CCRF, in October 2013, Mr. Miller sent an email to Dr. Priestley asking whether she would be interested in working with his organization.[19]Mr. Miller indicated that Dr. Priestley had been referred by Michael Flores, the CEO of Bretton Woods, Inc., a consulting firm that counts the payday lending industry among its clients.[20]

Mr. Flores has been a stalwart defender of the payday lending industry, testifying before Congress and submitting comments to federal agencies arguing payday lenders should be left unregulated.[21]Mr. Miller contacted Dr. Priestley because she was working with Mr. Flores on a study for the Online Lenders Alliance, a trade association for the payday lending industry.[22]Bretton Woods paid Dr. Priestley $13,000 for her work on that project.[23]After an initial phone call, Mr. Miller laid out his purpose for hiring Dr. Priestley (emphasis added):

As we discussed, we are interested in answering some of the “$64 questions” about payday lending, namely whether: (a) variation in state rollover regulation affects borrower welfare outcomes, and (b) variation in rollover usage affects borrower welfare outcomes.

And

I would like to start from scratch on the analysis and produce two papers (or possibly one consolidated paper) of academic quality, peer-reviewable, that would respond to these issues. In my model, you would be the PI and would publish the paper under your name. We are here to help but want the paper to be yours.

And

I have a budget that can support a decent stipend and defray any expenses. […] Please give this some thought, and then let’s speak later in the week about your interest and what you would need to make this worth your while.[24]

Mr. Miller and Dr. Priestley eventually signed a contract and a non-disclosure agreement.[25]

“Please give this some thought, and then let’s speak later in the week about your interest and what you would need to make this worth your while.”

CCRF agreed to pay $30,000 for Dr. Priestley to produce the paper.[26]Mr. Miller then supervised all aspects of Dr. Priestley’s study: he provided the data for the analysis; he suggested background literature to guide the analysis; and he directed how to build Dr. Priestley’s analytical models. Following the initial setup, Mr. Miller provided detailed feedback and then proceeded to rewrite entire sections of the paper.

Mr. Miller’s close involvement appears to contradict what he said under oath during a deposition with CfA as a part of CfA’s lawsuit to obtain the emails. In April 2016, he said:

We’ve never funded any research where we specifically sought to have the result be either pro or anti industry. We funded research where the investigator performed an investigation and the chips fell where they might and in some cases, the results have been quite mixed.[27]

In this case, Mr. Miller wanted Dr. Priestley to investigate and conclude that consumers who repeatedly roll over their payday loans actually benefit from the loans.[28]Mr. Miller believed that an earlier paper by Neil Bhutta of the Federal Reserve and two coauthors had settled the debate about the benefits of payday loans in general – that the average recipient of a payday loan does not suffer a lower credit rating after receiving a payday loan.[29]Mr. Miler wanted Dr. Priestley to investigate specifically whether serial payday loan customers suffer depreciated credit scores:

To understand the importance of this paper and what I visualize as its contribution to science, it’s worth viewing Bhutta et al. (and nearly all of its predecessor science) as looking at mean effects; that is, Bhutta determines that users as a whole aren’t any better or worse off as a result of using payday loans. This makes perfect sense, as he explains, because the loans are small and the borrowers were in pretty bad financial shape to begin with. But we know, or at least suspect, that there is a distribution of outcomes. Okay, we know it. For most borrowers, having a payday loan either makes little difference or is welfare-enhancing. But there is that pesky left tail. Policymakers are appropriately focused on the left tail. They want to know: what do those people look like, and how did they get there? So, we’d like to take a deeper dive into how heavy users differ from others, both in terms of their welfare outcomes, as well as whether it is possible to identify loan applicants at the pre-loan stage who have a propensity to [get] “stuck” in the product for a long time.[30]

The welfare of serial borrowers was also the subject of the earlier CCRF-funded study, written by Dr. Fusaro and Dr. Cirillo. Their paper was titled, Do Payday Loans Trap Consumers in a Cycle of Debt?, and it concluded, unsurprisingly, that “high interest rates on payday loans are not the cause of a ‘cycle of debt.’”[31]

Miller Guides Priestley’s Study

Following his initial direction, Mr. Miller shaped Dr. Priestley’s paper at every stage of the writing process. He provided data from three payday lending companies so Dr. Priestley could begin building her analytical models.[32]On December 1, 2013, Dr. Priestley told Mr. Miller that she had compiled “interim results” that she wanted to share with him.[33] After Dr. Priestley sent a preview of her findings to Mr. Miller on December 4, 2013, he provided substantive feedback and directed Dr. Priestley to proceed in a modified fashion. He wrote, in part:

When we speak tomorrow, I’d like to convince you that we need to explore changes in credit scores for individual borrowers before and after borrowing — not within-state changes in scores over time — as the dependent variable.

And

It’s really important to get the concept right before we start the analysis, and for now I’d rather that we focus on the specifications rather than trying to write the paper.[34]

“I am here to serve.”

Dr. Priestley responded: “…you don’t have to ‘convince me’ – I am here to serve. I just want to make sure that what I am doing analytically is reflecting your thinking.”[35]

On December 9, 2013, amid a discussion regarding how to adjust her analysis, Dr. Priestley asked Mr. Miller (emphasis added):

I am “bucketing” the change in Vantage score to group those with an “adverse” outcome as we discussed. Would you rather seethe bucketing logic based on percentiles (e.g., lowest 10%, lowest 20%, etc) or standard deviations (.5 std below the mean, 1 std below the mean, etc)?[36]

Mr. Miller responded that he preferred the percentage change method.[37]Later that day, Dr. Priestley sent updated results to Mr. Miller.[38]

Dr. Priestley’s initial findings concluded that borrowers’ credit scores decreased by an average of 6 points from 2006 to 2007 and did not change between 2008 and 2009.[39] Mr. Miller was not satisfied with the results, and he responded that they needed to adjust the analysis.[40] Mr. Miller told Dr. Priestley that they needed to “find a way to control for the subjects’ pre-test” credit score.[41] Dr. Priestley then recruited a colleague to help her build out a new model to address Mr. Miller’s request to bury her finding that overall credit scores decreased.[42]

The idea that overall credit scores decreased between 2006 and 2007 does not appear anywhere in Dr. Priestley’s paper. Instead, this sentence appears in her conclusion: “Overall, a majority of payday borrowers experienced an increase in their credit scores over the time period studied.”[43]One table in the paper’s appendix does include the overall decrease, but it is never discussed in the narrative.[44]

Abstract Mr. Miller Emailed to Dr. Priestley:

“The discourse surrounding payday loans has recently focused sharply on consumers’ propensity to “roll over” these loans, which are typically two-week, very-high-cost advances. The industry’s principal regulator has suggested that this sustained usage may be harmful to consumers. Exploiting interstate differences in rollover regulation, and using administrative data supplied by three lenders for 28,000 borrowers that have been matched to credit scores from a national credit reporting agency, I explore the effectiveness of various regulatory schemes in improving consumer outcomes in the years following initial payday borrowing. I also evaluate the effects of sustained payday-loan usage irrespective of regulatory scheme. I find that, while state regulation has a small effect on longer-term usage patterns, consumers whose borrowing is unrestricted by regulation fare better than consumers in the most restrictive states, after controlling for initial financial status. I also find that longer-term borrowers (three months or more) have better outcomes than consumers whose borrowing is concluded in one month or less. These findings raise significant policy questions and suggest the appropriateness of further study of actual consumer outcomes before the imposition of new regulation at the federal level.”

Abstract Published in Dr. Priestley’s Paper:

“Using payday-lender administrative data matched to borrower credit attributes from a national credit bureau, I find that borrowers who engage in protracted refinancing (“rollover”) activity have better financial outcomes (measured by changes in credit scores) than consumers whose borrowing is limited to shorter periods. These results are robust to an alternative definition of a “rollover” that ignores out-of-debt periods of 14 days between successive loans. Also, exploiting interstate differences in rollover regulation, I find that, while regulation has a small effect on longer-term usage patterns, consumers whose borrowing is less restricted by regulation fare better than consumers in the most restrictive states, controlling for initial financial condition.These findings directly contradict key assumptions about this market, raise significant policy questions for federal regulators, and suggest the appropriateness of further study of actual consumer outcomes before the imposition of new regulatory rollover restrictions.”

By January 22, 2014, Dr. Priestley had finished her analysis of the data. She wrote to Mr. Miller on that day, “At this stage – my focus was to get the tables (analysis) completed – then focus on the writing . . . take a look and let me know what analytical edits are still needed.”[45]After a few more emails back and forth, they appear to have settled on the appropriate data analysis.[46]

On January 30, 2014, Mr. Miller sent an email to Dr. Priestley with the subject line, “Abstract – First Pass – Subject to Further Thought and Your Input.”[47]The email contained a draft of an abstract for the paper. The final published abstract for the paper contains nearly all of the ideas expressed in Mr. Miller’s first draft, including the findings he articulated.[48]

On February 3, 2014, Dr. Priestley responded to the abstract email by stating she had “made good progress” and expected “to have a completed draft” to him before the end of the week.[49]Mr. Miller then told her to take extra time, since the nature of the findings indicated she would be subjected “to intense scrutiny from opponents of the industry.”[50]He said he wanted “to make sure we have anticipated their criticisms.”[51]

On February 17, 2014, Dr. Priestley delivered a “full draft of the paper.”[52]Two days later, Mr. Miller responded with 21 numbered paragraphs of suggested edits.[53]They include many detailed suggestions, which demonstrate the farcical nature of Dr. Priestley’s claim that CCRF “did not exercise any control” over the paper. Mr. Miller’s comments also state directly that policymakers were the intended audience for the paper. Specifically, Mr. Miller wrote, in part (emphasis added):

4. The paper should start off with a discussion of payday loans, not with a discussion of Dodd-Frank or “abusive” practices. Actually, this material doesn’t seem to belong at all. What is a payday loan? Who uses them, how do they use them, and why is this population potentially vulnerable? Why do rollovers matter? What is the potential harm from rollovers? What previously unanswered questions does your paper answer, and why are your questions important to policymakers?You need to set the paper up better. I get to the third paragraph before you even start this discussion. It needs to start with a bang. It now starts with kind of a thud. This is blockbuster stuff. You put me to sleep before I got to the “good stuff.”

7. The literature survey needs to be more comprehensive with respect to the evidence on rollovers. You need to discuss Fusaro and Cirillo (2011) and Mann (2013).[54]

8. Critically, although you cite Bhutta, Skiba and Tobacman (2013), for several possible adverse demographic findings, you do not cite the paper for its principal finding, which is that payday loans have a “precise zero” long-run effect on consumers’ financial well-being(italics in the original). This paper is and remains the “gold standard” for whether payday loans are harmful or helpful to consumers. The results found by these investigators fully take into account all of the sustained usage of payday loans criticized by the CFPB. The CFPB simply chooses to ignore it. There is no other academic research that relates sustained usage with consumer outcomes, and there is no economically demonstrated “need” to protect consumers either from multiple loans or longer usage terms. The Mann paper effectively destroys the notion that consumers are being misled, as alleged by Pew, into taking out a short-term product for long-term use. These relationships need to be developed in the text.

“A key audience for the paper will be highly educated but innumerate policymakers.”

10. I would like you to add at least one or two extra paragraphs on the VantageScore in general. You should cover what the score is, what its principal components are, and how it works. This can be a relatively brief discussion, although it is an opportunity to introduce the weights applied to the components, which are relevant to our population. Then, you should explain – and this is really critical – why VantageScore is an appropriate outcome variable for this kind of study. You can borrow from Bhutta et al. if you need to do so here, but the key is to give a clear indication of the wisdom of selecting this outcome variable in preference to others than you might have chosen (such as, for example, simply using defaults in the style of Desai). You should anticipate and counter the argument made by Pew that these scores are either too uniformly low or irrelevant for this population.

12. In general, I find the tables are not self-explanatory. By that I mean that a reasonably skilled reader cannot turn to a table and immediate tell what is being represented, either because the column and row headings are omitted, too abbreviated, or too cryptic. This should be remedied, including by the addition of footnotes where necessary. Go overboard on explaining in the footnotes how to read the tables, giving express examples if necessary. A key audience for the paper will be highly educated but innumerate policymakers.

13. The material starting on page 4 is where some key “beefing up” of the text is required. Here, you need to explain not only what the tables say, but also what they mean.As a policymaker, what am I supposed to take away from this?

17. I think the “default” discussion is somewhat confusing. Going back to the original purpose of this inquiry, opponents of payday lending hypothesize that defaults are harmful for consumers, although there seems to [sic] no data to support that hypothesis. We want to test this hypothesis and report the results of our testing. (At least one possible counterfactual is that defaults are actually welfare-enhancing because the borrower gets to keep the loan principal and collection efforts are largely ineffective. This may explain what is going on.) In any event, we once again launch directly into the numbers without explaining why we are making this inquiry and why anyone should care about it. We then don’t connect the results to the original question.[55]

Miller Takes Over the Writing

On March 4, 2014, Dr. Priestley sent Mr. Miller an updated draft.[56]Five days later, Mr. Miller sent 11 paragraphs of suggested edits.[57]Again, his specific instructions highlight how the paper was designed to advance the payday lending industry’s political agenda:

From a structural standpoint, there is something amiss here, and I realize that it’s a monster of my own creation. The paper is supposed to be about payday rollovers. It has that title, and that is its indeed its thrust.[58]

Mr. Miller again directed Dr. Priestley to discuss papers on which Mr. Miller had worked (emphasis added):

Please go back and look at my previous memo of 2/19 regarding Fusaro and Cirillo (2011) and Mann (2013).These are the canonical works on rollovers, but you don’t even bother mentioning them in this section. The later references in the paper should be deleted. You should specifically discuss not only that they studied these matters, but what and how they studied, and what they concluded. Please look at my previous comments. At multiple points in the paper it feels as if you are citing Einstein for his cake recipe instead of for his general theory of relativity.[59]

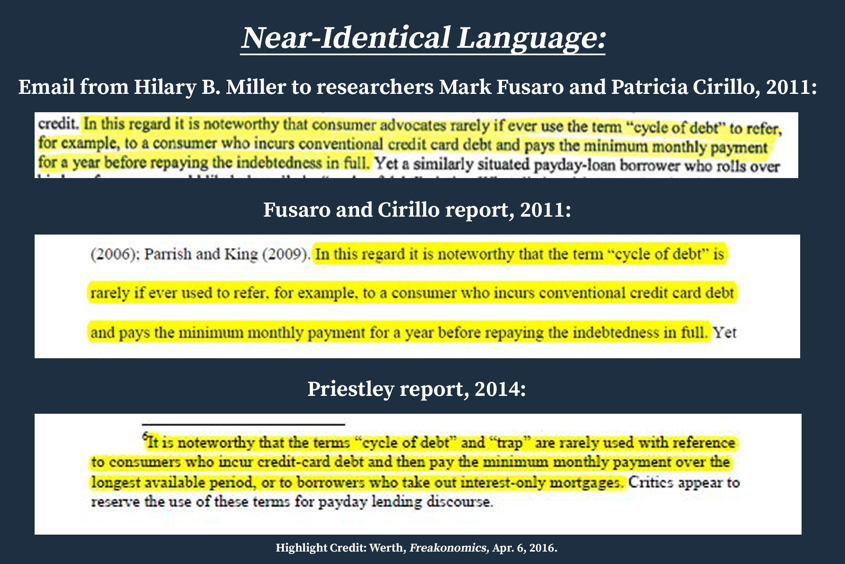

Mr. Miller also directed Dr. Priestley to eliminate a term loathed by the payday lending industry, the “cycle of debt”:

5. In general, we do not accept the notion that a “cycle of debt” even exists, and I would appreciate it if you would delete all references to this term, unless you are rebutting its existence.[60]

In fact, the final version of the paper includes a footnote about the cycle of debt that reads:

It is noteworthy that the terms “cycle of debt” and “trap” are rarely used with reference to consumers who incur credit-card debt and then pay the minimum monthly payment over the longest available period, or to borrowers who take out interest-only mortgages. Critics appear to reserve the use of these terms for payday lending discourse.[61]

As Freakonomics pointed out in an article about CfA’s previous report, the first sentence of this footnote is nearly identical to one that Mr. Miller directed Dr. Fusaro and Dr. Cirillo to include in their 2011 paper.[62]Mr. Miller also directed Dr. Priestley to make several other edits (emphasis added):

The lit survey also needs a broader discussion of the CFPB “White Paper,” to which you allude but which you summarize only for its non-data-based findings. I can fix this in your next draft, but it would be easier for you to do it yourself. Again, state what they studied, how they studied it, and what the conclusions were that were supported by their data. You can then discuss separately the political conclusions included in the White Paper that were not supported by the data. I can help you with this if you want.[63]

And

Thanks for all your hard work. It is really coming along. I am hoping that I can start line-editing your next draft soon and that we can finish the paper this month.[64]

“I am focusing now primarily on editorial efforts.”

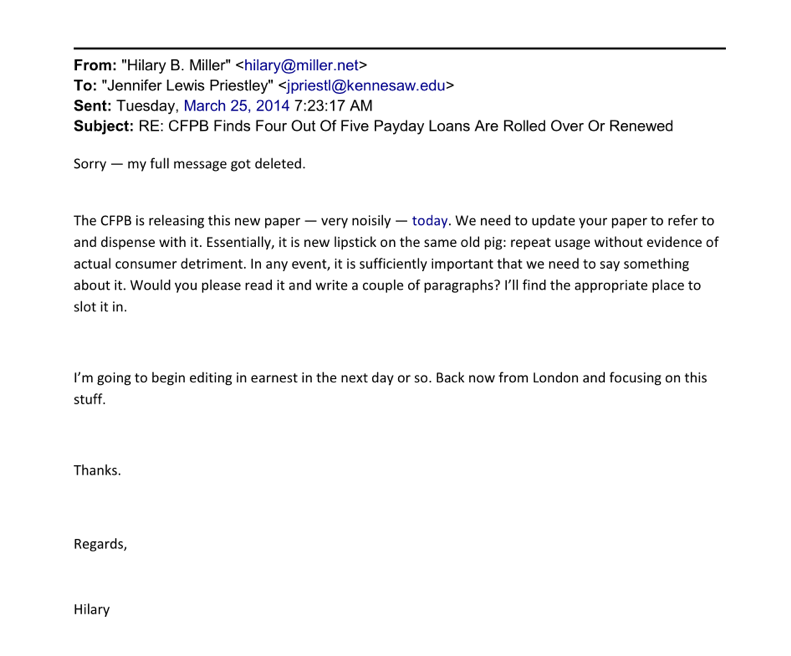

On March 17, 2014, Dr. Priestley sent Mr. Miller an updated draft.[65]On March 22, he wrote, “Got it. I am focusing now primarily on editorial efforts.”[66]On March 25, he forwarded a press release from the CFPB, writing (emphasis added):

The CFPB is releasing this new paper — very noisily — today. We need to update your paper to refer to and dispense with it. Essentially, it is new lipstick on the same old pig: repeat usage without evidence of actual consumer detriment. In any event, it is sufficiently important that we need to say something about it. Would you please read it and write a couple of paragraphs? I’ll find the appropriate place to slot it in.[67]

He also told her that he was “going to begin editing in earnest.”[68] Dr. Priestley then sent Mr. Miller additional language to address the CFPB paper.[69]On March 26, he wrote (emphasis added):

Thanks for this. It’s more prolix than what I think is appropriate, but I’ll skinny it down and insert it in the paper.

Recall that both Mann and Fusaro & Cirillo use a “window” much wider than yours to define a “rollover.” In doing so, they are capturing an economic, rather than literal, refinancing. The theory is that, if the consumer needs to re-incur the debt before reaching his or her next payday, the consumer lacked the means to repay the debt in full from recurring cash inflows. This is something of an effort to bend over backwards to accommodate our antagonists but nevertheless captures an issue that is important to policymakers.[70]

On April 1, Mr. Miller sent his first fully-edited draft of the paper to Dr. Priestley without even bothering to track his changes.[71]He also wrote, in part (emphasis added):

I have completed a preliminary round of editing your paper. I have spent quite a bit of time on it and have been as careful as possible. The principal changes I have made are organizational and editorial, while attempting to the greatest extent possible to leave your original substance intact. I think the paper is now more concise and less verbose, better organized and a bit more linear in how it reaches its conclusions. I have beefed up some portions of the paper with additional sources and explanations, while deleting a fair amount of the dated literature discussion.

The changes are numerous and fairly extensive. This draft is not redlined. Please review it and feel free to make any further additional changes (or reversions) you feel strongly about.

And

Another item – and this is really big – is that you will need to test your results for robustness under a different definition of “rollover” that comports with the new CFPB paper (CFPB 2014) – i.e., 14 rather than 2 days. I leave to you just how much you need to do to persuade yourself that the results don’t really change. Once you are satisfied, you can update the footnote to state what procedures you followed and why you are persuaded.

And

This is a terrific paper. When it is done, you are going to be famous and your phone will ring off the hook. We are actually talking about a “quiet” release to a few peer reviewers and including the CFPB in the review group. We want them to believe that the results are honest, verifiable and, most importantly, correct. Thanks so much for your help. Please try to finish this up quickly so that we can get it in peer review circulation.[72]

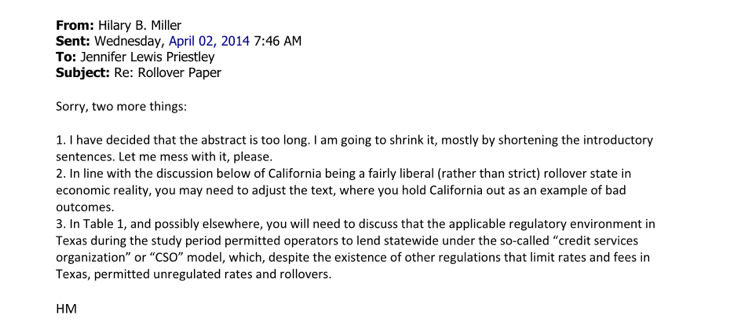

On April 2, Mr. Miller added, “I have decided that the abstract is too long. I am going to shrink it, mostly by shortening the introductory sentences. Let me mess with it, please.”[73]

Mr. Miller continued to send more edits. On April 4, 2014, he wrote, “I have made some changes to the paper (sic) only major substantive change is material related to the CSO model and CFSA[74]‘best practices.’ Here’s the revised draft.”[75]On April 5, 2014, Mr. Miller sent six more suggested edits, concluding, “Will await your response and incorporate these matters in a redlined revised draft later today or tomorrow.”[76]After a back and forth, Mr. Miller sent Dr. Priestley a revised draft on April 7, 2014.[77]

The Payday Lending Cronyism Network

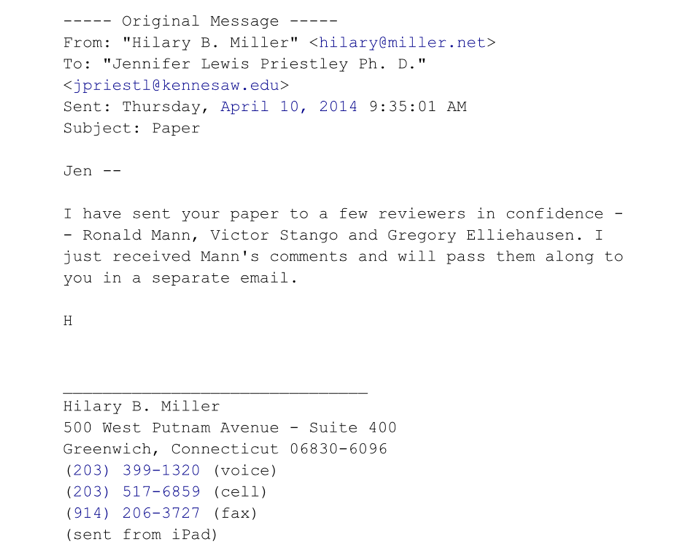

After Mr. Miller had shaped the paper to his liking, on April 10, 2014, he told Dr. Priestley that he had forwarded it to other CCRF-funded academics to ask them to provide comments on the paper.[78]Mr. Miller sent the paper to three researchers: Ronald Mann, Gregory Elliehausen, Ph.D., and Victor Stango, Ph.D.[79]Mr. Miller had repeatedly implored Dr. Priestley to cite a 2013 paper by Mr. Mann, who is a Columbia law professor.[80]Mr. Miller knew Mr. Mann, because CCRF had paid to collect the data used in the 2013 paper.[81]As Freakonomics uncovered, “Mann’s paper does not disclose the fact that Miller hired and provided payment” to a consultant to collect the survey data for Mann’s research.[82]

Dr. Elliehausen, who is a Principal Economist at the Federal Reserve, has written several articles defending the payday lending industry.[83]At least one of his articles was funded by the Community Financial Services Association of America (CFSA), a payday lending trade association.[84]

Dr. Stango, who is a professor at the University of California, Davis, previously served on the board of Mr. Miller’s CCRF.[85]Between 2006 and 2015, Dr. Stango received more than $185,000 for his role.[86]Notably, one of Dr. Stango’s former research assistants appears to have conducted the initial research for Dr. Priestley’s paper. In one of Mr. Miller’s early emails to Dr. Priestley from October 29, 2013, he wrote:

These data have been in the hands of a junior investigator for several months, and I have pulled the plug on this project because it was not progressing satisfactorily and it was impossible to get even professionals (let alone policymakers) to make sense out of her choice of methodology.[87]

The junior researcher was apparently an economist named Danielle Sandler. According to her LinkedIn page, Dr. Sandler received her Ph.D. in June 2012 from UC Davis, where she was a research assistant for Dr. Stango and other professors.[88]Following graduation, she worked as an independent research consultant for CCRF from October 2012 to March 2013.[89]In one email, Mr. Miller encouraged Dr. Priestley to “paraphrase liberally from Sandler’s paper and to use some of her additional work that’s not in the paper.”[90]Dr. Priestley even asked Mr. Miller if she should include Dr. Sandler as a second author on the paper, but ultimately they decided not to credit her work.[91]Dr. Sandler is now a Senior Economist at the U.S. Census Bureau.[92]

Each of the three payday-lender-funded reviewers provided comments to Dr. Priestley.[93]In forwarding Dr. Elliehausen’s comments, Mr. Miller wrote: “I’m glad we didn’t wait too long to get these comments – they are not that helpful. We’re not going to start from scratch. Take what you want from them.”[94]

Mr. Miller forwarded Dr. Stango’s comments, and wrote, in part (emphasis added):

Here are Victor’s comments. They are more comprehensive, more oriented toward the analytical presentation, and more useful than Ronald’s— but also more daunting to implement. On reflection, I agree with him regarding the value of reversing the order of the two principal findings. As with the previous comments, view these as suggestions rather than commands. Feel free to email or call him directly if you want to discuss it with him.[95]

In forwarding Mr. Mann’s comments, Mr. Miller wrote, “Just ignore his comments about Caskey and the big picture question. He doesn’t get it. That’s not what we sought to study and I don’t think it matters as a policy matter anymore.”[96]On April 21, 2014, Dr. Priestley sent her comments responding to Mr. Mann by saying in part, “in the interest of ‘version control’ I can let you be the keeper of the working draft.”[97]

Mr. Miller, however, apparently wanted to address Mr. Mann’s overall comments. On May 12, 2014, Mr. Miller wrote in an email to Dr. Priestley, in part:

- I am working on an edited version of your paper. I should have it done today. I will send it back to you for your further review, but I think this is very nearly the end.

- I have spoken with Ronald Mann about some of the default-related issues we unearthed in this database. He is an extremely sharp guy and he would be a great collaborator with you on the “second study,” if you would be interested in working with him. In any event, I would like to share the combined dataset with him. Would you please arrange to send him a link or other means by which he can FTP or download it? His email address is rmann@law.columbia.edu.[98]

One month later, on June 7, 2014, Mr. Miller still was trying to address Mr. Mann’s concerns. He said in an email to Dr. Priestley, “Want to talk to you about the ‘default’ issue and see if we can coordinate with Mann.”[99]Apparently, it took some time to address Mr. Mann’s comments. On June 25, 2014, Dr. Priestley apologized for not sending her feedback about defaults sooner.[100]Mr. Miller responded that she had answered the wrong question (emphasis added):

This is useful, but for the most part it answers the wrong question. In the last few paragraphs, it begins to zero in on the issue we care about.

As a reminder, we are not interested in predicting defaults, or in who defaults. Rather, we are investigating whether the fact of having defaulted makes a difference to a consumer’s welfare after the default. We are making this because the CFPB has asserted that defaults are harmful to consumers, which really seems unlikely given that the consequences of most defaults are that the borrower retains the loan proceeds without being subject to collection action and without any bureau derogatory report.

So, it would be useful to look at changes in credit scores (or other outcome variables, such as delinquencies on other debts, which are likely to be similar) in the time following default. Perhaps we could compare these changes with the changes in scores of non-defaulters with similar initial credit scores.

Would you mind taking another stab at this, please? Sorry if we miscommunicated about it.[101]

Amid a back and forth, Mr. Miller outlined a synopsis of the entire working arrangement (emphasis added):

We want to control for non-default factors, which in this context means to me comparing outcomes for defaulters with the outcomes [sic] similarly initially scored non-defaulters. I leave the methodology to you.[102]

Beyond the reviewers, Mr. Miller had asked Dr. Priestley to send the data from the study to “another consultant who will be using it for a completely unrelated purpose.”[103]Dr. Priestley then sent the data to Arthur Baines, Vice President, Co-Practice Leader of Financial Economics, at Charles River Associates.[104]Mr. Baines subsequently published papers in 2015 and 2016 for the Community Financial Services Association of America (CFSA), arguing that the CFPB’s proposals to rein in payday lenders “are likely to impact the lenders both negatively and significantly.”[105]

Producing an Industry-Backed Paper

On July 24, 2014, Joi Sheffield, a lobbyist for CFSA delivered Dr. Priestley’s study to David Silberman, the Associate Director for Research, Markets, and Regulation at the CFPB.[106]After the meeting, Ms. Sheffield sent an email to Mr. Miller, and two CFSA executives, with the subject line, “The package has been delivered,” writing:

He was appreciative of the manner in which delivered and stated that. He glanced at the first few pages and said he was looking forward to reading it. I made the points you conveyed to me Hilary and told him I hope that this would encouraged (sic) the bureau to dig deeper into this area.[107]

Mr. Miller forwarded the email to Dr. Priestley, writing:

The subject line is a not-very-secret coded message to reflect that your paper was hand-delivered this morning to David Silberman, who is Associate Director for Research, Markets and Regulation at the CFPB. They have known it was coming, I think, but this is their first look. They will likely duplicate and circulate it internally, and your phone will soon start to ring. I am meeting with Jesse Leary, who is their lead economist on payday, at the end of next week, and this will also be a topic for discussion then.[108]

In subsequent emails, Dr. Priestley told Mr. Miller that no one from the CFPB had followed up about the paper. On November 5, 2014, Mr. Miller wrote:

We received no feedback from the CFPB about your paper. Although they told us they would be calling you with comments and suggestions, apparently they did not. I think it is reasonable to assume that they either have none, or that they want to hold their fire until after the paper is “out” so that they can get a publicity benefit from making their criticisms public. Either way, it is now approaching time to release the paper.

We would like to work with you on the mechanics of release. My question for you is whether your institution will issue a press release regarding the publication of your paper – which we would be happy to draft for their review. Once released, you could put the paper up on SSRN and circulate it to various journals for publication.

Happy to have a call to discuss, but the $64 question is whether the press release could come from your end rather than ours. We would greatly prefer this approach. The question is timely and important, so it seems that the school might want to crow over it.[109]

Ms. Sheffield, for her part, appears to have violated lobbying disclosure laws.[110]She never disclosed on her lobbying disclosure forms that she lobbied the CFPB on behalf of CFSA.[111]

After the CFPB apparently declined to review the paper, Dr. Priestley and Mr. Miller worked out the logistics for releasing the paper publicly. Mr. Miller introduced Amy Cantu, Communications Director for CFSA, to Dr. Priestley to help with the release.[112]On November 19, 2014, Ms. Cantu sent a draft of a press release to Dr. Priestley and KSU media relations personnel for them to review.[113]

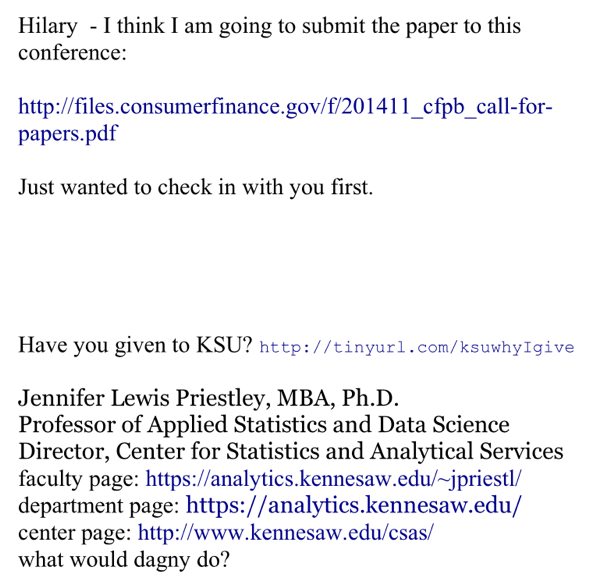

On December 5, 2014, Dr. Priestley asked Mr. Miller to send her a final copy of her own paper, so that she could upload it to the Social Science Research Network (SSRN) for public distribution.[114]Mr. Miller responded by sending Dr. Priestley the Word and PDF versions of her own paper.[115]He also wrote, “Please use the abstract verbatim as the SSRN abstract, if you don’t mind doing so.”[116]After Dr. Priestley uploaded the paper to SSRN, she asked Mr. Miller, “Would you like for me to load the paper in other locations as well? My website? Our Dept website? Forward to Microbuilt? FactorTrust?”[117]

It is unclear whether Mr. Miller responded. On December 30, 2014, Dr. Priestley submitted the paper to a CFPB conference about consumer finance.[118]Before she submitted the paper, which appears to have not been accepted, she first sought permission from Mr. Miller.[119]

Using the Paper to Defeat Regulations

As the emails indicate, Mr. Miller commissioned Dr. Priestley’s paper in order to wield it as a weapon in his industry’s battle against the CFPB. In 2012, the CFPB began the long process of studying payday loans, to determine whether to adopt regulations limiting the industry’s ability to prey on low-income consumers. In January 2012, the CFPB began oversight of the industry, and in April 2013, released a study that concluded:

The current repayment structure of payday loans and deposit advances, coupled with the absence of significant underwriting, likely contributes to the risk that some borrowers will find themselves caught in a cycle of high-cost borrowing over an extended period of time.[120]

In November 2013, shortly after Mr. Miller first reached out to Dr. Priestley, the CFPB began accepting complaints against payday lenders – a prelude to adopting regulations.[121]In March 2014, the CFPB released another study about payday loan rollovers that found, among other things, “Over 80% of payday loans are rolled over or followed by another loan within 14 days (i.e., renewed).”[122]

Mr. Miller had warned Dr. Priestley about the study, and he instructed her to add language to her paper to counter the conclusions reached by the CFPB.[123]Dr. Priestley eventually drafted two paragraphs for Mr. Miller to slot into her paper to rebut the agency.[124]Dr. Priestley’s final paper contains just one sarcastic sentence about the CFPB paper, “More recently, however, CFPB (2014) generally avoids normative statements or unsubstantiated conclusions regarding the welfare implications of rollovers.”[125]

While the CFPB worked to introduce regulations concerning payday lenders, the industry employed several tactics to thwart the agency’s agenda. For instance, on June 19, 2014, the trade publication American Banker published an article explaining how one company had hired a former top CFPB official, Rick Hackett, to conduct an analysis of the industry’s data:

The twist here is that the man hired to run the industry-funded research project knows where the bodies are buried, so to speak, after having served as CFPB’s assistant director responsible for the Office of Installment and Liquidity Lending Markets.[126]

The study that Mr. Hackett eventually produced served as the industry’s explicit rebuttal to the CFPB studies. The study was published in February 2016, and Mr. Hackett later summarized:

The Report therefore suggests that an intervention that is certain to eliminate the storefront industry may not make legal or economic sense. The CFPB should allow the product to continue, perhaps in an amortizing installment form, where high rate installment loans are permitted by state law. Where that is not allowed, a sequence of up to six payday loans should be allowed, with borrowers guaranteed an amortizing installment exit plan if they hit the six-loan trigger.[127]

Before Mr. Hackett had completed the study, however, the CFPB had reached its next step to regulate the industry. In March 2015, the CFPB announced that it was “considering proposing rules that would end payday debt traps by requiring lenders to take steps to make sure consumers can repay their loans.”[128]Mr. Hackett’s study then served as ammunition for the industry to try to hold back the CFPB.

In April 2016, the CFPB released another study that examined the excessive fees payday loan borrowers rack up while using payday loans.[129]Two months later,on June 2, 2016, the CFPB issued its proposed rule to rein in payday lenders.[130]The rule was exactly what the industry had feared, and payday lending companies called on their congressional allies to beat back the rule.[131]Despite these efforts, the CFPB issued the final rule in October 2017.[132]

Payday Lenders Strike Back

After the head of the CFPB, Richard Cordray, stepped down on November 24, 2017, payday lenders gained a new ally at the agency.[133]President Trump appointed the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Mick Mulvaney, to lead the agency temporarily.[134]Before joining the administration, Director Mulvaney had served as a member of Congress, where he was a strong ally of the payday lending industry.[135]

After Director Mulvaney took over, the CFPB began working to roll back payday lending protections. In January 2018, the CFPB announced that it was going to reconsider the payday lending rule that it had adopted just three months earlier.[136]In late October, the agency announced that in January 2019 it would reconsider the “the ability-to-repay provisions” of the payday lending rule.[137]On December 6, 2018, the Senate confirmed a new CFPB director, Kathy Kraninger, who previously had worked for Director Mulvaney at OMB.[138]On February 6, 2019, the CFPB released its proposal to rescind the 2017 payday lending rule.[139]The proposal cites Mr. Mann’s study extensively.[140]

Now that the CFPB is being run by allies of the industry, payday lenders have renewed their reliance on Dr. Priestley’s study to beat back CFPB regulations.[141]On January 17, 2018, the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) cited Dr. Priestley’s study in a blog post,entitled “7 Reasons to Oppose the Federal Payday Loan Rule.”[142]The article argues, among other things, that borrowers appreciate payday loans and that state laws are sufficient to regulate the industry. Previously, in 2016, CEI had published a study, authored by Mr. Miller, that claimed the CFPB’s payday lending rule would cut off access to credit and harm consumers.[143]

Conclusion

Payday lenders profit from a uniquely predatory business model, which is predicated on the weakness of government regulation. Because payday lenders rely on such ruthless tactics, few academics or researchers are willing to defend the industry. As a result, payday lenders have been forced to produce their own fawning studies by funding complicit academics and editing the papers themselves.

As this report reveals, Mr. Miller used his position as the industry’s academic-in-residence to produce a Potemkin defense of the payday lending industry that could be used to cudgel government regulators. Dr. Priestley’s willingness to produce the paper was not only an abrogation of her professional responsibilities, but it also provided payday lenders with ammunition in the industry’s war against the CFPB. Dr. Priestley allowed one of the most notorious industries in America to cash in on her reputation for just $30,000.

Exhibits

[1]The emails released by KSU are available at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5737855-EMAILS-Redacted-BETWEEN-PRIESTLEY-and-MILLER-1.html.

[2]Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Public Law 111-203, 111th Congress, July 21, 2010, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/4173/.

[3]Payday Loan Facts and the CFPB’s Impact, Pew Charitable Trusts, January 14, 2016, available athttps://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2016/01/payday-loan-facts-and-the-cfpbs-impact.

[4]Id.; Stacy Cowley, Payday Lending Faces Tough New Restrictions by Consumer Agency, The New York Times, October 5, 2017, available athttps://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/business/payday-loans-cfpb.html.

[5]Rick Cohen, Fighting Payday Lenders State by State and at the Federal Level, Nonprofit Quarterly, May 7, 2014, available athttps://nonprofitquarterly.org/2014/05/07/fighting-payday-lenders-state-by-state-and-at-the-federal-level/.

[6]https://www.atu.edu/profiles.php?name=mfusaro&menu=business;https://www.linkedin.com/in/marc-fusaro-9a2a1964;http://www.cypress-research.com/about.htm; Marc Anthony Fusaro and Patricia J Cirillo, Do Payday Loans Trap Consumers in a Cycle of Debt?, SSRN, November 16, 2011, available athttps://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1960776.

[7]Academic Deception, Campaign for Accountability, November 2015, available at https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2930174/288230891-Academic-Deception.pdf. Stephen J. Dubner, Are Payday Loans really as Evil as People Say, Freakonomics, April 6, 2016, available athttp://freakonomics.com/podcast/payday-loans/.

[8]The trade association was previously known as the Payday Loan Bar Association. See https://www.eventbrite.com/e/short-term-loan-bar-association-2018-annual-meeting-tickets-49148203600; Christopher Werth, Tracking the Payday-Loan Industry’s Ties to Academic Research, Freakonomics, April 6, 2016, available at http://freakonomics.com/podcast/industry_ties_to_academic_research/; Deposition of Hilary B. Miller, Consumer Credit Research Foundation, Civil Action File No. 2015CV262308, Superior Court of Fulton County, State of Georgia, April 27, 2016, pg. 50, available athttps://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4367923/CfA-Deposition-of-Hilary-B-Miller-04-27-2016.pdf;Academic Deception, Nov. 2015, Exhibit Y.

[9]Jennifer Lewis Priestley, Payday Loan Rollovers and Consumer Welfare, SSRN, December 5, 2014, (hereafter: Priestley, 2014) available athttps://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5686189-Priestley-Miller-Payday-Loan-Rollvers-and.html.

[10]Id.

[11]Id.

[12]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, January 30, 2014, attached as Exhibit A.

[13]Priestley, 2014.

[14]https://campaignforaccountability.org/work/open-records-request-payday-lending-study-commissioned-kennesaw-state-university/.

[15]Id.

[16]https://campaignforaccountability.org/campaign-for-accountability-seeks-answers-about-payday-lending-study-by-kennesaw-state-university-professor/.

[17]The emails released by KSU are available at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5737855-EMAILS-Redacted-BETWEEN-PRIESTLEY-and-MILLER-1.html.

[18]Deposition of Hilary B. Miller, Apr. 27, 2016, pg. 8, available athttps://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4367923/CfA-Deposition-of-Hilary-B-Miller-04-27-2016.pdf.

[19]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, October 25, 2013, attached as Exhibit B.

[20]http://www.bretton-woods.com/about.html.

[21]G. Michael Flores, Testimony: Examining Consumer Credit Access, Concerns, New Products and Federal Regulations, U.S. House Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit Hearing, July 24, 2012, available athttps://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:vL0IqE6ZaHwJ:https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hhrg-112-ba15-wstate-mflores-20120724.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us; G. Michael Flores, Commentary: The Pew Charitable Trusts Report Fraud and Abuse Online: Harmful Practices in Internet Payday Lending, Bretton Woods, November 2014, available athttp://www.bretton-woods.com/assets/Flores_Commentary_-_Pew_Report_of_Fraud_and_Abuse_-_Final_-_November_21__2014.pdf; Letter from G. Michael Flores to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, May 22, 2013, available athttps://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/federal/2013/2013-deposit_advance_products-c_18.pdf; G. Michael Flores, Testimony, Are Alternative Financial Products Serving Consumers?, U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection, March 26, 2014, available athttps://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FloresTestimony32614FICP.pdf.

[22]Mr. Flores’s study relied on Dr. Priestley’s paper throughout his final analysis. SeeG. Michael Flores, The State of Online Short-Term Lending,Online Lenders Alliance, July 2015, available athttp://onlinelendersalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/2015-Bretton-Woods-Online-Lending-Study-FINAL.pdf;http://onlinelendersalliance.org/about/board-of-directors/.

[23]Funded Grants and Contracts FY 14 July 2013 – June 2014, Kennesaw State University, July 29, 2014, pg. 9, available athttps://research.kennesaw.edu/about/proposals-awards.php.

[24]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, October 29, 2013, attached as Exhibit C.

[25]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, November 6, 2013, attached as Exhibit D.

[26]Kayla Coggin, Payday Lenders Lose Open Records Lawsuit, Courthouse News Service, June 20, 2018, available athttps://www.courthousenews.com/payday-lenders-lose-open-records-lawsuit/;Funded Grants and Contracts FY 14 July 2013 – June 2014, Kennesaw State University, Jul. 29, 2014.

[27]Deposition of Hilary B. Miller, Apr. 27, 2016, pg. 16.

[28]This conclusion is expressed in the original abstract that Mr. Miller sent to Dr. Priestley on January 30, 2014. See Exhibit A.

[29]Neil Bhutta, Paige Marta Skiba, and Jeremy Tobacman, Payday Loan Choices and Consequences, Vanderbilt Law and Economics Research Paper No. 12-30, October 11, 2012, available athttps://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2160947.

[30]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, November 5, 2013, attached as Exhibit E.

[31]Fusaro and Cirillo, SSRN, Nov. 16, 2011.

[32]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, November 3, 2013, attached as Exhibit F.

[33]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, December 1, 2013, attached as Exhibit G.

[34]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, December 4, 2013, attached as Exhibit H.

[35]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, December 4, 2013, attached as Exhibit I.

[36]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, December 9, 2013, attached as Exhibit J.

[37]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, December 9, 2013, attached as Exhibit K.

[38]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, December 9, 2013, attached as Exhibit L.

[39]Id.

[40]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, December 9, 2013, attached as Exhibit M.

[41]Id.

[42]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, December 11, 2013, attached as Exhibit N.

[43]Priestley, 2014, pg. 23.

[44]Id.pg. 30.

[45]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, January 22, 2014, attached as Exhibit O.

[46]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, January 25, 2014, attached as Exhibit P.

[47]SeeExhibit A.

[48]Priestley, 2014.

[49]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, February 3, 2014, attached as Exhibit Q.

[50]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, February 3, 2014, attached as Exhibit R.

[51]Id.

[52]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, February 17, 2014, attached as Exhibit S.

[53]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, February 19, 2014, attached as Exhibit T.

[54]As noted below, Mr. Miller funded and edited the 2011 paper, and he worked with Mr. Mann on the 2013 paper.

[55]Id.

[56]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, March 4, 2014, attached as Exhibit U.

[57]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, March 9, 2014 attached as Exhibit V.

[58]Id.

[59]Id.

[60]Id.Mr. Miller’s criticism of the term “cycle of debt” continues for more than half a page.

[61]Priestley, 2014.

[62]Werth, Freakonomics, Apr. 6, 2016.

[63]SeeExhibit V.

[64]Id.

[65]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miler, March 22, 2014 attached as Exhibit W.

[66]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, March 22, 2014, attached as Exhibit X.

[67]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, March 25, 2014, attached as Exhibit Y.

[68]Id.

[69]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, March 26, 2014, attached as Exhibit Z.

[70]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, March 26, 2014, attached as Exhibit AA.

[71]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 1, 2014, attached as Exhibit BB.

[72]Id.

[73]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 2, 2014, attached as Exhibit CC.

[74]CFSA is an acronym for the Community Financial Services Association of America, a payday lending trade association.

[75]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 4, 2014, attached as Exhibit DD.

[76]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 5, 2014, attached as Exhibit EE.

[77]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 7, 2014, attached as Exhibit FF.

[78]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 10, 2014, attached as Exhibit GG.

[79]Id.

[80]https://www.law.columbia.edu/faculty/ronald-mann.

[81]Werth, Freakonomics, Apr. 6, 2016.

[82]Id.

[83]https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/gregory-elliehausen.htm.

[84]Edward C. Lawrence and Gregory Elliehausen, A Comparative Analysis of Payday Loan Customers,Wiley Online Library, April 13, 2008, available athttps://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1465-7287.2007.00068.x.

[85]https://gsm.ucdavis.edu/faculty/victor-stango; Werth, Freakonomics, Apr. 6, 2016.

[86]https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/200919672.

[87]See Exhibit C.

[88]https://www.linkedin.com/in/danielle-sandler-02405343.

[89]Id.

[90]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, December 20, 2013, attached as Exhibit HH.

[91]Id.; Priestley, 2014.

[92]https://www.linkedin.com/in/danielle-sandler-02405343.

[93]KSU released the emails from Mr. Miller to Dr. Priestley, but they did not release the attachments containing the reviewers’ comments. KSU did release a document containing Dr. Priestley’s responses to Professor Mann’s comments.

[94]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, May 1, 2014, attached as Exhibit II.

[95]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 22, 2014, attached as Exhibit JJ.

[96]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, April 10, 2014, attached as Exhibit KK.

[97]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, April 21, 2014, attached as Exhibit LL.

[98]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, May 12, 2014, attached as Exhibit MM.

[99]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, June 7, 2014, attached as Exhibit NN.

[100]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, June 25, 2014, attached as Exhibit OO.

[101]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, June 25, 2014, attached as Exhibit PP.

[102]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, June 25, 2014, attached as Exhibit QQ.

[103]See Exhibit NN.

[104]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Arthur Baines, Date Redacted, attached as Exhibit RR.

[105]Arthur Baines, et. al., Economic Impact on Small Lenders of the Payday Lending Rules Under Consideration by the CFPB, Prepared for the Community Financial Services Association of America, May 12 2015, available athttps://www.crai.com/sites/default/files/publications/Economic-Impact-on-Small-Lenders-of-the-Payday-Lending-Rules-under-Consideration-by-the-CFPB.pdf; Arthur Baines, et. al., Economic Impact on Storefront Lenders of the Payday Lending Rules Proposed by the CFPB, Prepared for the Community Financial Services Association of America, October 7, 2016, available athttp://www.crai.com/sites/default/files/publications/Economic-Impact-on-Storefront-Lenders-of-the-Payday-Lending-Rules-Proposed-by-the-CFPB.pdf.

[106]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, July 24, 2014, attached as Exhibit SS; https://www.linkedin.com/in/joi-sheffield-25a3514; Sheffield Brothers, Third Quarter 2014 Lobbying Disclosure Report on behalf of Community Financial Services Association of America, Secretary of the Senate, Office of Public Records, available athttps://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=068CE6A8-C024-4695-AC39-95EECF665B32&filingTypeID=73;https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/the-bureau/bureau-structure/research-markets-regulation/.

[107]SeeExhibit SS.

[108]Id.

[109]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, November 5, 2014, attached as Exhibit TT.

[110]See Letter from Daniel Stevens to Julie E. Adams, Secretary of the Senate, and Karen L. Haas, Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives, February 15, 2019, available at https://campaignforaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/CfA-LDA-Complaint-Payday-2-25-19.pdf.

[111]Sheffield Brothers, 2011-2018 Lobbying Disclosure Reports on behalf of Community Financial Services Association of America, Secretary of the Senate, Office of Public Records, accessed at https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=selectFields&reset=1.

[112]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley and Amy Cantu, November 6, 2014, attached as Exhibit UU.

[113]Email from Amy Cantu to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, Hilary B. Miller, et. al, November 19, 2014, attached as Exhibit VV.

[114]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, December 5, 2014, attached as Exhibit WW.

[115]Email from Hilary B. Miller to Jennifer Lewis Priestley, December 5, 2014 attached as Exhibit XX.

[116]Id.

[117]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, Date Redacted, attached as Exhibit YY.

[118]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to CFPB_ResearchConference@cfpb.gov, December 30, 2014, attached as Exhibit ZZ.

[119]Email from Jennifer Lewis Priestley to Hilary B. Miller, Date Redacted, attached as Exhibit AAA; https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/cfpb-research-conference/2015-cfpb-research-conference/.

[120]Payday Loans and Deposit Advance Products, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, April 24, 2013,available athttps://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201304_cfpb_payday-dap-whitepaper.pdf.

[121]Press Release, CFPB Begins Accepting Payday Loan Complaints, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, November 6, 2013, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-begins-accepting-payday-loan-complaints/.

[122]Kathleen Burke, Jonathan Lanning, et. al., CFPB Data Point: Payday Lending, CFPB Office of Research, March 2014, available athttps://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201403_cfpb_report_payday-lending.pdf; Press Release, CFPB Finds Four Out of Five Payday Loans Are Rolled Over or Renewed, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, March 25, 2014, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-finds-four-out-of-five-payday-loans-are-rolled-over-or-renewed/.

[123]SeeExhibit Y.

[124]SeeExhibit Z.

[125]Priestley, 2014.

[126]Kevin Wack, Payday Loan Industry Mounts Challenge to CFPB Research, American Banker, June 19, 2014, available athttps://www.americanbanker.com/news/payday-loan-industry-mounts-challenge-to-cfpb-research.

[127]Rick Hackett, Searching for “Harm” in Storefront Payday Lending, CounselorLibrary, March 2016, available at https://www.counselorlibrary.com/insights/article.cfm?articleID=931.

[128]Factsheet, The CFPB Considers Proposal to End Payday Debt Traps, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, March 26, 2015, available athttps://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201503_cfpb-proposal-under-consideration.pdf.

[129]Online Payday Loan Payments,Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, April 2016, available athttps://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201604_cfpb_online-payday-loan-payments.pdf.

[130]Press Release, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Proposes Rule to End Payday Debt Traps, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, June 2, 2016, available at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/CFPB_Proposes_Rule_End_Payday_Debt_Traps.pdf.

[131]Federal Regulators Propose Restrictions on Payday Loans, Tribune News Services, June 2, 2016, available athttps://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-payday-lending-rules-20160602-story.html; Ian McKendry, Bipartisan Group of Lawmakers Urges CFPB to Ease Up on Payday Rule, American Banker, September 30, 2016, available athttps://www.americanbanker.com/news/bipartisan-group-of-lawmakers-urges-cfpb-to-ease-up-on-payday-rule.

[132]Press Release, CFPB Finalizes Rule to Stop Payday Debt Traps, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, October 5, 2017, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-finalizes-rule-stop-payday-debt-traps/.

[133]Letter from Richard Cordray to CFPB Employees, November 24, 2017, available athttps://www.politico.com/f/?id=0000015f-efff-d90d-a37f-ffff72670000.

[134]Renae Merle, The CFPB Now Has Two Acting Directors. And Nobody Knows Which One Should Lead the Federal Agency, Washington Post, November 24, 2017, available athttps://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2017/11/24/the-cfpb-now-has-two-acting-directors-and-nobody-knows-which-one-should-lead-the-federal-agency/.

[135]Special Report: Mick Mulvaney is a Payday Industry Puppet, Allied Progress, January 17, 2018, available athttps://alliedprogress.org/research/special-report-mick-mulvaney-is-a-puppet-for-payday-lenders/.

[136]Press Release, CFPB Statement on Payday Rule, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, January 16, 2018, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-statement-payday-rule/.

[137]Press Release, Public Statement Regarding Payday Rule Reconsideration and Delay of Compliance Date, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, October 26, 2018, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/public-statement-regarding-payday-rule-reconsideration-and-delay-compliance-date/.

[138]Emily Sullivan, Senate Confirms Kathy Kraninger as CFPB Director, NPR, December 6, 2018, available at https://www.npr.org/2018/12/06/673222706/senate-confirms-kathy-kraninger-as-cfpb-director.

[139]Press Release, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Releases Notices of Proposed Rulemaking on Payday Lending, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, February 6, 2019, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-releases-notices-proposed-rulemaking-payday-lending/.

[140]12 CFR Part 1041, Docket No. CFPB-2019-0006, Payday, Vehicle Title, and Certain High-Cost Installment Loans, February 6, 2019, available athttps://www.consumerfinance.gov/documents/7241/cfpb_payday_nprm-2019-reconsideration.pdf.

[141]Irina Ivanova, What Kathy Kraninger’s Nomination Might Mean for the CFPB, CBS News, June 21, 2018, available athttps://www.cbsnews.com/news/kathy-kraninger-nomination-to-cfpb-bcfp-means-consumers-are-on-their-own/.

[142]Daniel Press, 7 Reasons to Oppose the Federal Payday Loan Rule, Competitive Enterprise Institute, January 17, 2018, available athttps://cei.org/blog/7-reasons-oppose-federal-payday-loan-rule.

[143]Hilary Miller, Ending Payday Lending Would Harm Consumers, Competitive Enterprise Institute, October 5, 2016, available athttps://cei.org/sites/default/files/Hilary_Miller_-_Ending_Payday_Lending_Would_Harm_Consumers.pdf.